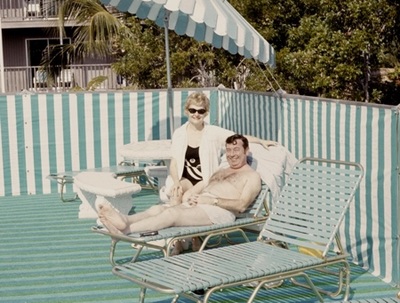

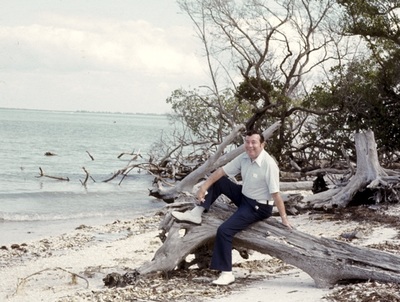

The 70's version of Dan at Christmas The 70's version of Dan at Christmas Of the many Christmas landscapes that I’ve experienced, none is as weird as Christmas in Florida. I was in college at the time in Virginia, and road-tripped with a friend down Interstate 95 to meet my parents in Orlando for the holiday. They’d decided that it might be fun to experience the yuletide under a palm tree. My parents, Millie and Jack Howe, are both from the Midwest, where Christmas is often frigid and rarely white. For much of my childhood we lived in St. Louis, with excursions for several years to the New York metro area and to eastern Pennsylvania where I went to high school - different places with a similar December climate. The family tradition was to stay home with the heat on, look skyward hopelessly for snowflakes, erect the three part fake Christmas tree the weekend after Thanksgiving, make a lot of cookies and load the underside of the tree with an embarrassing pile of gifts that we would open ritually in our pajamas on Christmas morning with Grandpa. It was a good tradition, despite the disappointment of cold without snow just about every year. Between St. Louis, New Jersey and Pennsylvania the holiday routine was consistent, so the idea of a Florida Christmas was just a small bit disturbing. But who was I to argue with Mom and Dad? Let’s go for it. My father was suffering with a rapidly advancing case of rheumatoid arthritis at this point in his life. He understood what the future might hold for him and I believe the Florida Christmas was his idea. He was trying to pack in as many adventures as he could before his physical condition would start to preclude simple things most of us take for granted like walking and buttoning one’s own shirt. We stayed in a small place in Orlando that was located in what used to be a citrus grove. In the back yard of the unit we were renting was a grapefruit tree, and the rental came with a basket-like thing with grabbers on a stick, the perfect tool to pull the Yule grapefruit down off the tree and have it drop nicely into the basket for easy retrieval. I still remember my father sawing out the grapefruit sections with a butter knife and marveling at how short the distance was between this particular fruit’s perch on its stem and its final disposition at the breakfast table, compared with the well-traveled and somewhat more road-worn orbs that we’d pick up in the produce section of the Schnuck’s back home. After breakfast we donned our Christmas shorts and t-shirts and headed to the then-new Walt Disney World theme park, where a series of larger-than-life cartoon characters greeted us dressed in what must have been stifling costumes of red velvet and white fur, the sound system all around piping in startlingly incongruous songs about sleighbells and snowmen while we wiped our brows in the warm sun between adventures in Space Mountain and Epcot. Part of that trip also involved a visit to Cypress Gardens, a now-anachronistic water resort in south-central Florida then widely known for its beautiful tropical gardens and water-skiing show featuring bikini-clad skiers. I daresay that moment represents the first and probably the last time I will see Santa Claus doing a spread-eagled leap off a ramp on a set of water skis while holding onto a tow rope from a powerboat. The best memories I have of the Florida Christmas were formed during the several days we spent on Sanibel Island, on the Gulf Coast near Ft. Myers, Florida. At that point Sanibel was still a mostly undeveloped island upon which existed a series of small homes and tiny motels and a sandy single two-lane roadway, the island heavily protected by stern land use regulations its citizens imposed on the building industry and by the eyebrow-raising toll exacted when crossing the causeway from the mainland. We decorated a croton plant with a few colored lights inside our tiny motel room and exchanged a few gifts, without Grandpa this time, to mark the day itself. But the island was much more a magical place than Disney World, with Santa’s gifts strewn all across the beach in the form of beautifully formed seashells, which we collected greedily, as if somehow they’d run out if we didn’t get them right away. The warm breeze off the Gulf stirred the palms, and flocks of seabirds passed overhead, looking to roost nearby in the “Ding” Darling Wildlife Preserve as the sun set below the horizon in the Gulf. Christmas dinner was simple fare from one of the local restaurants, the building covered with bougainvillea that had been decked out with multi-colored Christmas lights, as if such a plant needed any more decoration than nature had already given it. Tropical as it was, this holiday was still Christmas, and we enjoyed each other and our treasure-trove of seashells. Then we folded our beach chairs, brushed the sand off our bare feet, and returned to our respective homes – me to Virginia to look for signs of white on the Blue Ridge come January, my sister to Bloomington, Indiana, and my parents back to St. Louis, where in the Italian section of the city every architectural feature of every house in every neighborhood was covered with as many colored lights as the owners could afford to buy and power, in celebration of the birth of the Christ Child. In keeping with this heritage, I try to keep some downward pressure on the ever-escalating property values in my own neighborhood by stringing lights on everything I can find in the yard and on the façade of my house during the season. I must apologize to those who think that the tasteful single candle in each window and the lovely wreath on the door constitute Christmas decorations. I respectfully disagree. This year apparently the squirrels have taken offense at my overindulgence. They ate through the wires on several of my strands, alas during a time when the electricity was off. As the temperature approaches 70, with 75 degrees predicted for Christmas Day, suddenly the Florida Christmas is closer in mind than it’s been in some time. I think my own family may be in shorts right here in Raleigh on our Christmas hike this year, much as my mother, father and sister were on Sanibel back when my father could still walk in the warm sand and button his own shirt. Somehow despite so many happy, chilly, snow-bereft years with my parents and my sister in our cozy home with the heat on, the holiday I seem to remember is the incongruous one. I still hold out hope for a white Christmas here in North Carolina, despite our warming climate. One year we actually almost had it. In a bizarre turn of events Wilmington, on the usually-warmer coast of North Carolina, was buried in a freak snowstorm on Christmas Eve, with snow extending west as far as Goldsboro, only to turn to a cold rain at the Johnston County line, about 40 miles east of Raleigh. Sigh. Without palm trees, grapefruits and seashells, the warm weather we've experienced recently is not quite as welcome this time of year in the Piedmont as it was on our Florida adventure. But it’s still Christmas, and enough lights have survived the squirrels to glisten through the rain outside the window and make me remember that, even though the Bing Crosby Christmas landscape of snowmen and sleigh bells is a pipe dream for us this year, the one we have is still pretty nice. It will be in the 70’s with a few thunderstorms predicted on the holiday, and I will walk with my family and neighbors on Christmas Eve in a t-shirt and a rain jacket down to the corner to see the live Nativity at the Hayes Barton Baptist Church. We’ll feel sorry for the wet burro and the little sheep, and the poor angels from the youth choir standing in the rain on top of the manger. We’ll still sing Christmas carols and give Luna a new dog toy, and we will all continue to wish for a white Christmas someday. This year I will also think about my parents’ wild idea to see Santa on water skis, the wonderful gift of seashells on Sanibel Island, the warm air and beautiful sunsets, and I will remember the two of them and miss them. Happy Christmas to all. May the New Year bring you peace and joy.

2 Comments

Photo credit: Phillip Capper (Flickr) Photo credit: Phillip Capper (Flickr) In 1989 my wife Loretta and I, and our friends Cece and Bill Ussler hiked 12 miles into the backcountry of Canyonlands National Park in search of an ancient cave painting – the All American Man. Recent radiocarbon dating of the pigments used in this ancient pictograph places its creation somewhere in the 14th century. Canyonlands is a landscape of sandstone, carved by wind and water into the kind of sculptural rocky shapes that Utah puts on its license plates. On our way we came upon an Anasazi cliff dwelling beneath a sandstone overhang. It was close to the trail, but there were no railings, no concrete walkways, no signs directing or restricting our access. It was as if we were ‘discovering its existence, as some early explorer in this part of the West did. I remember feeling hesitant, approaching as if trying to avoid stepping on a grave in a cemetery. Beneath a giant rock were the remains of a house where people had lived, raised children, stored food, built fires to warm themselves - almost 800 years ago. As I stood in the remains of the kiva, I was stunned by the magnitude of time that separated me from the last person who lived here. It is the same feeling I often get as I look up toward Orion’s belt on a clear winter night - smallness in the face of time and distance. But in such places this gulf of time and space does not isolate me from the owner of my kiva or from the Big Bang, but somehow connects me to them, the separation between the corporal and the spiritual becoming a thin veil. There is a Celtic Christian term for the rare locales where the distance between heaven and earth collapses. They are called “thin places”, and here in the kiva the wall of time and culture that separates me from the Anasazi, the Ancient Ones, who so mysteriously disappeared from this landscape, fades. This is a built place. So often people seek thin places in nature – waterfalls and craggy peaks, dark forests and seashores. But we humans have built many landscapes, interior and exterior, that similarly pare the distance between the sacred and the solid. Visit the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC at dusk and you will understand. Another such place is the Flight 93 National Memorial in southwestern Pennsylvania, or St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. Great architecture or landscape architecture can do this. But a simple cannon placed in a Virginia meadow can do the same. My friend Paul Morris, a landscape architect from Atlanta, said this in the context of a conversation about sacred places: “Places are static – meaning comes from people.” Sometimes the physical environment does not have to be striking to be powerful – a multi-community greenway in Memphis, Tennessee is not so much about the bicycles and pedestrians who may use it as it is about a single gunshot in April 1968 and the racial divide that has characterized the community, and how the path knits parts of the community together that have been separated ever since. What Paul is saying is that a place must have meaning to people in their own lives to capture a sense of spirituality beyond its physical space. I’ve felt this on the summit of Mt. Rogers in Virginia, the highest point in the Commonwealth. The final climb to the summit is not difficult. There are no views from the top, just a large rock with a USGS marker embedded in it surrounded by spruce and fir trees. But the approach to the summit is through a dense remnant of the Canadian-zone vegetation that once covered much of the East and Midwest in the wake of the last ice age. Here in the Southern Appalachians such forests are fast disappearing and are limited to the highest, coldest elevations. This forest is somehow quieter than the rest of the oak-hickory forest that surrounds the peak. Everything is moss-covered. It is dark, even on a bright day, and smells of balsam, like Christmas. Its meaning for me is wrapped in every fairy story I experienced as a child and with my own children as an adult, lands of mystery and strange creatures – wizards and Wookies. It reminds me of how colored lights on a dark night make me feel at that time of year. The tactile quality of the moss is comforting, like a blanket. God, or thousands of years of forest succession, created this place. A human built a trail here so I can experience it, but otherwise the hands of people have contributed little to this thin place, but there are many skillful designers packing meaning into landscapes throughout the world. Some are grand and historic, inspiring, like Andre le Notre’s Avenue des Champs-Élysées terminating in the dramatic Arc de Triomphe in Paris. Some are contemporary and personal even as they draw a crowd, like Anish Kapoor’s Cloudgate sculpture in Chicago. In it you can see yourself and the skyline of the city, reflected together. Alfred Runte, in his excellent book National Parks – The American Experience, makes the case that the National Park movement started in this country as an attempt to capture and preserve the soul of the new nation before it was overwhelmed with industry and commerce. The leaders who advocated for the preservation of special landscapes set out to create temples to remind us of what differentiated America from Europe with its grand cities and architecture. What they preserved started with the great Western landscapes that defined what America meant to its citizens at the time – the romantic notion of freedom within God’s creation. For the intervening 100+ years, the Park Service has wisely expanded this notion to preserve not just that moment in history, but a pastiche of soul-markers along the way – battlefields, homes, factories, monuments – that have meaning for people. It is no accident that I’ve discovered many thin places in my wanderings through the park system, from the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, DC to a craggy outcrop on the Appalachian Trail in Virginia overlooking the James River valley. When we are at our best, we humans have the ability to build mystical places that can rival the emotion engendered by a view of Half-Dome or the feeling of the mist rising from Niagara Falls. This mystery arises from our shared stories, good and bad, of freedom and conflict, wisdom and blindness. If we pay close attention, maybe we can learn from the stories of people who lived long before us, and also from the thin places not created by the hand of man, understanding in some small way how a copse of conifers atop Virginia’s highest peak can transport us to another world.  This year the Japanese maples (generally Acer palmatum species) have had an extraordinary fall. Because the weather has been warm and wet, the Japanese maples have hung on even past the emptying of the foliage on the pecan trees - usually the last to drop their leaves. Their spectacular color, combined with the fact that only they, the crepe myrtles (Lagerstroemia spp.) and some oaks are still hanging on into the first days of December, helped me pay particular attention to them this year on my walks around the neighborhood in the morning with Luna the dog. Scientists say that most trees are photoperiodic - the length of the day relative to the night rather than the temperature is what triggers the changes in metabolism that begin the process resulting in the spectacular colors that we see - yellow, orange, red, purple. Japanese maples are typically small trees, sometimes very small in the case of the "dissectum" varieties - the cutleaf Japanese maples. All of them have lovely shapes, and this year luminous red or red-orange color. I have several varieties in my small yard. The winner of the eye-popping color contest this year is a purple-leafed maple (Acer palmatum atropurpurea) whose leaves come out purple in the spring and gradually fade to a dark green/red before transitioning to a dazzling scarlet this fall. The other surprise was a small seedling of the coral bark maple (Acer palmatum Sango-kaku) whose normally bright yellow fall leaves have a decidedly red-pink cast this year, unlike its parent tree. I feel fortunate to be able to see this - fall must be an entirely different experience for people who are sight-impaired - and even more fortunate to have noticed this and paid attention to it over the past few weeks. We move at a rapid pace through our world - on trains or buses, but mostly in this country in our cars. The amount of time we are not either flinging ourselves headlong through our network of highways, or moving back and forth in a small space in our offices or workplaces or homes is small. But if you choose to spend more of your day moving through the landscape at a walking pace, so much more is revealed that would otherwise have been a blink in passing through the windshield at 40 or 50 miles per hour. For me, the revelation at this pace this year has been the proliferation and immense beauty of the Japanese maples planted in people's yards along my path through this part of Raleigh. The richness of their color and the emphasis it brings to the shape of the tree against what is otherwise now a dull green or brown landscape is dramatic, and I feel as if I've been given a gift because Luna pulls me out on extended travels at walking pace in my world. I am reminded of my experience hiking the Appalachian Trail, where this gift was drawn out over 5 months in a journey that led through the mountain chain from Georgia to Maine, from winter to spring to summer to fall. Almost all long-distance hikers struggle to describe the experience after they've returned to the life of fast and slow, driving and sitting. An extended experience at 2 miles per hour is an opportunity to see what you have never seen before - the wildflower called a showy orchis hiding in a wedge of rock at a switchback, the particular color green that the forest takes on in April that can only be described as early spring green, as the buds on the deciduous trees slowly unfurl into leaves, the quick movement that turns what appears to be a twig into a swift litlle lizard, dashing for cover. It is hard to explain how much more detail is available in the landscape at walking pace, and how repeated experiences with it teach us things. I hiked the AT at a time before access to hand held communication devices kept us connected wherever we go. We found that over time walking in the forest we developed a sensitivity to our surroundings, particularly the weather, that was nearly as accurate as we could have accessed via smartphone today. The smell of the air, the color of the sky, the clouds and how they were changing would tell us a lot about what the weather was to be like the next day. I can still recall the deadness of the air, the immense stillness, that preceded the remnants of Hurricane David before it slammed into us in New England. I also still recall the absurdly good-natured group packed tightly into a three-sided shelter that night as it rained sideways, our tent flys and ponchos strung across the open side of the tent in a futile attempt to keep it from raining inside. One hiker pulled out a harmonica and launched into what would become the improvised "Leaky Shelter Blues". Humans were designed to move at walking pace, and I am reminded of the observation skills we are born with as I spend extended hours at this speed. Our bicameral vision gives us perspective, shape and spatial awareness, and a sense of distance and movement. We also hear more and can look at and listen to longer something that might catch our attention in the landscape. I like operating my automobile as much as the next person - a road trip is more fun for me than for my wife Loretta, but I would never have noticed the Japanese maples this year at 60 miles per hour. Safety requires that we scan the landscape ahead of us quickly when we drive - looking for hazards. If we're lucky we can glance at something along the way, but it is gone before we get a chance to really LOOK at it. I look forward to seeing what the winter will bring. With so many trees around here, the summer obscures much of what we've built, and in the winter a lot of how people have chosen to live in this place is exposed. Luna and I will set off at our two, maybe three mile-per-hour pace and watch for it as we go. |

AuthorDaniel Howe lives in Raleigh, NC. He's interested in a lot of things so this blog is all over the place. Archives

May 2018

Categories |

City Planning / Public Process

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed