Ralph Stanley, image courtesy The Bluegrass Situation Ralph Stanley, image courtesy The Bluegrass Situation Ralph Stanley died Thursday at the age of 89, just a few days after I returned from a visit to the National Park Service’s Blue Ridge Music Center near Galax, Virginia. The Music Center exists to celebrate the music that Ralph Stanley and his brother Carter helped popularize – a folk tradition that spans at least 7 generations here in this country, and even further back in the Gaelic and Scots ballad traditions in the British Islands. The Stanley Brothers, and their southwestern Virginia neighbors A. P. Carter and his musical family, took “hillbilly” music to the national stage beginning in the 1940’s when Ralph and Carter formed a band, the Stanley Brothers and the Clinch Mountain Boys, and began performing in and around Bristol VA and Johnson City, TN. Ralph Stanley never used the term “bluegrass” to describe his music. Kentucky native Bill Monroe and his band the Bluegrass Boys popularized the term (a sound which, ironically, is often credited to NC banjo player Earl Scruggs). Stanley is perhaps best remembered for the “high, lonesome” sound his clear tenor emphasized, a sound that rings clear in mountain hollows from Madison County, NC near Asheville north to Bristol and Kingsport in Tennessee, and east to Galax, Virginia and Mount Airy, North Carolina. It is the musical theme of a hard life in a beautiful place. The title of Stanley’s 2009 autobiography, “Man of Constant Sorrow” says a lot about the bittersweet world of the Southern Appalachian mountains, a place of breathtaking natural beauty, strong families, tragedy and struggle – the perfect mash for a rich world of art in music and craft. Last year on a long-distance bike ride in southwestern Virginia, not far from Stanley’s original home on Big Spraddle Branch, I stopped at the A. P Carter homestead, home of the famous Carter Family, listened to a string band perform on the porch, and even sat in Johnny Cash’s easy chair (Cash married June Carter, daughter of Maybelle Carter and niece of A.P. Carter). I’ve been playing this music for 25 years and the experience of being at the Carter home, and riding through the mountain valleys that inspired their music gave me chills. Similarly, last week at the Music Center on the Blue Ridge Parkway, I was able to listen to Galax, VA native Dori Freeman warm the crowd up for the Steep Canyon Rangers, and Freeman’s voice was once again rich with pain and love and anger, notes in her original songs inflecting up or breaking an octave down – the same plaintive call from the hills I remember from listening to friends sing in my time in Madison County. There is a hardness here, a life of disappointment and struggle and love and family and nature all wrapped up together and aching to emerge in song from so many who have lived in this land. Basically everyone up here is a musician. Every day at the Music Center people gather in the breezeway (in good weather) or in the luthier’s shop (in bad) to unpack guitars and mandolins and dobros and dulcimers and fiddles and banjos and basses from well-work cases to crank through a few hours of “Are You Washed In The Blood?”, “Shady Grove”, “Cotton-Eyed Joe”, “Cluck Old Hen”, and a few hundred other songs that everyone in the circle can play along with once the leader announces the key. Those that don’t play, sing. And they know all the words. They are young and old – sometimes very old - and sometimes very young. I have a friend here in Raleigh whose 13-year-old daughter plays the fiddle in the traditional style and plays rings around most people three times her age. This is back-porch music, music where you need to set aside a room to put the instrument cases when you hold a pot luck, music that works as well in a capella harmony out front of the grocery store as it does with a full string band. Mountains and hollows, branches (creeks), balds and coves…this is the landscape that raised Tommy Jarrell (he lived in Round Peak – about 15 miles from the Music Center), and Doc Watson (his home in Deep Gap is about 40 miles down the Parkway). In the springtime they sing about the “Wildwood Flower”, in the winter “The Fields Have Turned Brown”. There are songs about hard work (“Coal Miner’s Blues”), and faith (“Little White Church”), about liquor (“Mountain Dew”) and love (“Gold Watch and Chain”), and about murder (“Little Omie Wise”, “Tom Dooley”) and death (“Will the Circle Be Unbroken”, “Bury Me Beneath the Willow”). Stanley is part of a disappearing generation. Doc Watson passed on in 2013. Earl Scruggs died in 2012. Tommy Jarrell left us in 1985. The music continues in hollows and hills surrounding the Blue Ridge Parkway…and among millennials. Someone on the radio the other day said that it’s hard to find new popular music that is not categorized as “Americana”. Think Avett Brothers, Allison Krause, Nickel Creek, The Head and The Heart. Bluegrass as a genre is still popular, and increasingly so around here. The International Bluegrass Music Association annual meeting and festival here in Raleigh drew over 180,000 people in 2014. I cannot remember a better live music concert, ever, than the one Canton, NC’s Balsam Range performed on the free stage on Hargett Street that year. Now distant from its founding traditions, country music covers the earth but it’s important to remember where the Nashville sound started – in the hills of home in the shadow of Clinch Mountain, somewhere around Big Spraddle Branch where Ralph and Carter Stanley started playing the old tunes they heard from their family and friends. Ralph Stanley had been famous among lovers of this music for decades before he reached a new audience in 2000 on the soundtrack of the movie “O Brother Where Art Thou” with his haunting a capella rendition of “O Death”, the story of an old man bargaining with death to “spare me over for another year.” He lost the bargain yesterday, but not before his high, lonesome sound worked its way into my head and that of countless others, forever. My latest sun is sinking fast, my race is nearly run My strongest trials now are past, my triumph has begun Oh come Angel Band, come and around me stand Oh bear me away on your snow white wings to my immortal home Oh bear me away on your snow white wings to my immortal home From “Angel Band” – traditional Appalachian Gospel tune Click below to view a live performance of "O, Death" from 2008:

1 Comment

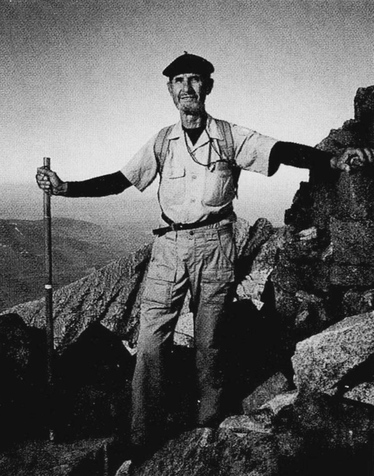

Nick Gelesko on Mount Katahdin in 1999 at age 79. Scanned photo of an image by photographer Chris Rainier for National Geographic Traveler magazine. Nick Gelesko on Mount Katahdin in 1999 at age 79. Scanned photo of an image by photographer Chris Rainier for National Geographic Traveler magazine. Nicholas Gelesko died on May 27. He would have been 95 years old in November of this year. He was a skinny old man with a Michigan accent who used to love to play tennis at his condo in Florida that he shared with his bride, Gwen. I first saw Nick when he wandered into a shelter site on the Appalachian Trail 38 years ago with a floppy white hat on his bald head, wearing a khaki shirt with epaulets and a shoulder patch (Appalachian Trail – Maine to Georgia), underneath a red rain jacket. He immediately sat down and started asking us about where we were from and about our names and families. And then he started telling stories in his characteristic Michigander accent about the Navy, and his long career as an engineer, about his several children and about so many other things that I have forgotten most of them, but I can still see him smiling and I can still hear him laugh at his own jokes. He was 58 at that time - already an old man in the reckoning of a 23-year old, but sturdy and athletic. Nick had recently retired from Westinghouse, where he worked as an engineer and, like many of us he was on the Trail in search of a new fulcrum point in his life. Off and on over the first two months on the A. T. my hiking buddy David Brill and I would regularly come across Nick and the group of people with whom he was hiking. It’s the culture of the Trail to be part of an interwoven social network of small groups, connected to the doings of others by trail registers located in each shelter. Long-distance hikers would sign in and note the day’s events, providing a collective diary of the community of walkers headed north. An extra day in a town would allow a group behind you to catch up. A particularly long day’s hike might allow you to overtake another group at a shelter whom you’d not seen in weeks. It was a series of departures and reunions, the cast thinning as the play wove on. Injuries and fatigue, internal demons and bad equipment took their toll, and at the psychological halfway point of the trail in Harper’s Ferry, only the durable and determined were left, generally a fraction of those who set out on Springer Mountain in Georgia for Maine. During his journey north through the Southern Appalachians, Nick’s wife Gwen had traveled from Michigan to hike with him for two weeks through the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, and his pace slowed to match hers. During the two weeks with her he fell far behind everyone who was part of his social network on the Trail. After she returned home upon completing their hike together, Nick began following my small group in the trail registers as he worked his way north. We had picked up a third member of our entourage by then. Paul Dillon was a tennis-and-ski bum from New Hampshire, long of leg and hair and younger than either of the two of us. We came across him early in our time in Pennsylvania and the connection stuck. Paul would stand on Katahdin with us that fall. The three of us were hiking through the Mid-Atlantic states by that time, and were traversing Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York in long strides, often walking in excess of twenty miles each day. For every twenty miles we’d hike, Nick would hike twenty-five in an attempt to catch up to us. This he did for 300 miles until he caught us on Bear Mountain near the Hudson River. We walked every step of the rest of the way together, the “Michigan Grand-dad” (his trail name) earning his keep by finding dozens of interesting ways to talk people out of their food. Any visitor to the Trail who happened to ask Nick about his hike would inevitably hear a poignant story about the endless steepness of the mountains, his advancing age and of course, the countless calories one had to expend to achieve this goal. By the end of the conversation the unsuspecting mark would have emptied every possible edible item from his car or pack to our benefit. Nick encountered a group of Harvard students on an outing at a shelter and came away with food for three days. We had fried chicken at one road crossing. Cold beer and potato salad at another. Nick was so good at this we turned his name into a verb: We’d speak about “geleskoing” lunch or a “geleskoing” a cold drink on a hot day from day hikers or campers. This odd group of hikers – two aimless wanderers from suburban DC, a youthful ski bum from New England who wanted to sing and play the guitar for a living, and the Michigan Grand-dad shared the remainder of the trek north to Mount Katahdin, cementing a lifelong friendship by sharing cold rains in the Berkshires, warm campfires in the Maine woods, and even a noteworthy short hike with a volunteer camp host in the White Mountains, a young woman who, taking advantage of the sunny day, decided to hike shirtless for a while. I can still see Nick’s eyebrows reaching high on his Midwestern bald pate as she ambled by. The story below I wrote in the year 2000, just after a 20th anniversary reunion hike in Maine organized by Dave, who by that time had written a book about our collective hike (…still in print: As Far As The Eye Can See, by David Brill, Univ. of Tennessee Press). This story was originally published in 2000 in Appalachian Trailway News, a magazine of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. I hope it tells you a little more about this man that we all loved. Gelesko The four of us had last stood here at the base of Katahdin twenty years ago—to the day. I had not seen or spoken to Nick Gelesko or Paul Dillon since we hugged and parted in September 1979. Like many Trail "families," we scattered after Katandin, beginning life stories we were now able to tell to each other for the first time. David Brill and I had rejoined the Trail a time or two together, but we'd let ten years get by since the last walk. A phone call from Tennessee last spring promised an opportunity for a paid trip to Maine. A reunion date was set. Plane reservations were coordinated from Raleigh, Knoxville, Seattle, Nassau, Northampton, and Ft. Myers. A remarkable convergence of schedules brought us all together, joined by fellow '79 A.T. hiker-friends Jim Black and Victor Hoyt. Paul, Dave, Nick and I were celebrating the 20th anniversary of the end of our thru-hike together, drawn back to the same center from which we had spun apart years ago. Nick Gelesko stood in Katahdin Stream Campground, looking up toward the summit, wearing the same khaki shirt he had worn the last time we'd made this climb. Same hat, too. Twenty years of advancing age takes a toll on muscle stamina and often deposits a few pounds in odd places, but, as a group, we had fared passably well. I'd gained about a pound a year; Dillon was the same lean, long-legged hiking machine he was in '79; Brill had apparently not gained any weight except in facial hair; and Gelesko stood trim and tanned, slim and athletic, as I'd remembered him. We had almost run up the Hunt Trail to Katandin's summit twenty years ago, fueled by five months of anticipation and conditioning. Confidence in our muscles and bones we learn from experience. We know our physical limits by reaching them. Exceeding those limits is a leap of faith, a blind dive off a high cliff. Competitive runners win races with their spirit, not their legs. Champion skaters visualize the perfect race... each turn, each stroke of blade on ice. They've won before the gun sounds. I wondered if Gelesko was climbing Katandin in this way now as he looked up at the peak in the glow of early morning. I remember discovering the extraordinary capacity of my own body as I worked my way into shape in the first six weeks of hiking on the A.T. I wrote in my journal then about discovering the "wonders of the lower leg," as somehow my body learned to compensate for fatigue in my quadriceps with greater strength in my calf muscles. Fatigue on the longest climbs means different parts of the body take over, one at a time, shouldering the load, until all that is left to pull you up the final climb to the top is your soul. All else is spent. In early morning, we set off from Katandin Stream, Dave, Paul, and Victor moved swiftly up the face of the mountain, while Jim, Nick and I walked more slowly and steadily onto the great granite slab. In the middle of the first substantial climb, Nick began to slow. His rest stops became more frequent. His jokes became fewer. His strong legs pushed up the mountain just ahead of me, but he struggled over the rock and was clearly fatigued as we emerged from the forest onto the face of the mountain, ready for the steepest part of the climb up to the plateau. In 1979, Nick had met his wife in Shenandoah National Park and hiked with her, his pace slowing to hers, and he'd fallen far behind us. He’d followed our progress in the Trail registers, hiking twenty-five miles a day to our twenty. After almost a month of this, he caught up with us at the Bear Mountain Bridge over the Hudson River. I was not about to leave him again. With a timely push from behind or a hand from above, Nick moved up the steepest part of the climb to the plateau. Open and clear on a beautiful day, the summit appeared close at hand across what appeared a relatively gentle slope to the top. Nick was clearly fatigued by this time, and we were actually more than a mile away, about six hundred feet below the summit. Whatever solace Nick took from the gentler slope was offset by the thinner air and his weakening muscles. I could see in his eyes that the final hundred vertical feet might defeat him. His breath was labored. His pace slowed even further. He was muttering to himself. We stopped. He planted his stick. He looked at the top, looked back at me, and set off, soul alone carrying him the rest of the way. It was late in the day for arrival at the summit of Katahdin – after noon. A large crowd of thru-hikers and others was preparing to descend. One person began to clap, and then all applauded for Nick as he stepped unsteadily atop the final rock. Dave, Paul, Nick and I posed for a photo once again on the summit of the Greatest Mountain. This time, only Nick had an extraordinary achievement to celebrate. As I write this I close my eyes and see the look of supreme happiness on the face of this man, in his black beret and khaki shirt, who, in 1979, traversed the A. T. with three companions less than half his age. He had emerged from surgery on his carotid artery just a few weeks before our reunion hike. At age 79, Nick Gelesko became my hero, again. At home, I try to do a good bit of hiking, a little running, some basketball. Sometimes when I challenge myself I am painfully aware of approaching middle age. The next time I find my body failing under the strain of a steep climb or an athletic competition, I won’t be visualizing the perfect race. I’ll be thinking of a skinny guy in a khaki shirt and beret smiling broadly, leaning on his hiking staff with the rocky ground falling away from him on all sides, blue sky behind. I’ll be hoping just a little of Gelesko’s soul will pull me up and over the top, too. |

AuthorDaniel Howe lives in Raleigh, NC. He's interested in a lot of things so this blog is all over the place. Archives

May 2018

Categories |

City Planning / Public Process

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed