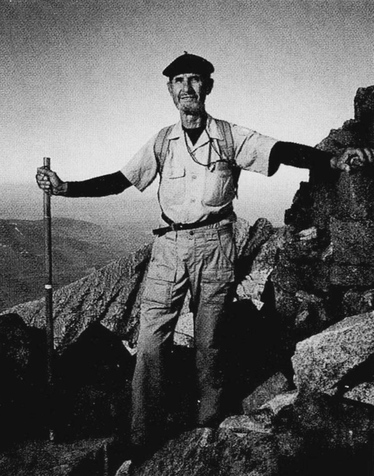

Nick Gelesko on Mount Katahdin in 1999 at age 79. Scanned photo of an image by photographer Chris Rainier for National Geographic Traveler magazine. Nick Gelesko on Mount Katahdin in 1999 at age 79. Scanned photo of an image by photographer Chris Rainier for National Geographic Traveler magazine. Nicholas Gelesko died on May 27. He would have been 95 years old in November of this year. He was a skinny old man with a Michigan accent who used to love to play tennis at his condo in Florida that he shared with his bride, Gwen. I first saw Nick when he wandered into a shelter site on the Appalachian Trail 38 years ago with a floppy white hat on his bald head, wearing a khaki shirt with epaulets and a shoulder patch (Appalachian Trail – Maine to Georgia), underneath a red rain jacket. He immediately sat down and started asking us about where we were from and about our names and families. And then he started telling stories in his characteristic Michigander accent about the Navy, and his long career as an engineer, about his several children and about so many other things that I have forgotten most of them, but I can still see him smiling and I can still hear him laugh at his own jokes. He was 58 at that time - already an old man in the reckoning of a 23-year old, but sturdy and athletic. Nick had recently retired from Westinghouse, where he worked as an engineer and, like many of us he was on the Trail in search of a new fulcrum point in his life. Off and on over the first two months on the A. T. my hiking buddy David Brill and I would regularly come across Nick and the group of people with whom he was hiking. It’s the culture of the Trail to be part of an interwoven social network of small groups, connected to the doings of others by trail registers located in each shelter. Long-distance hikers would sign in and note the day’s events, providing a collective diary of the community of walkers headed north. An extra day in a town would allow a group behind you to catch up. A particularly long day’s hike might allow you to overtake another group at a shelter whom you’d not seen in weeks. It was a series of departures and reunions, the cast thinning as the play wove on. Injuries and fatigue, internal demons and bad equipment took their toll, and at the psychological halfway point of the trail in Harper’s Ferry, only the durable and determined were left, generally a fraction of those who set out on Springer Mountain in Georgia for Maine. During his journey north through the Southern Appalachians, Nick’s wife Gwen had traveled from Michigan to hike with him for two weeks through the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, and his pace slowed to match hers. During the two weeks with her he fell far behind everyone who was part of his social network on the Trail. After she returned home upon completing their hike together, Nick began following my small group in the trail registers as he worked his way north. We had picked up a third member of our entourage by then. Paul Dillon was a tennis-and-ski bum from New Hampshire, long of leg and hair and younger than either of the two of us. We came across him early in our time in Pennsylvania and the connection stuck. Paul would stand on Katahdin with us that fall. The three of us were hiking through the Mid-Atlantic states by that time, and were traversing Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York in long strides, often walking in excess of twenty miles each day. For every twenty miles we’d hike, Nick would hike twenty-five in an attempt to catch up to us. This he did for 300 miles until he caught us on Bear Mountain near the Hudson River. We walked every step of the rest of the way together, the “Michigan Grand-dad” (his trail name) earning his keep by finding dozens of interesting ways to talk people out of their food. Any visitor to the Trail who happened to ask Nick about his hike would inevitably hear a poignant story about the endless steepness of the mountains, his advancing age and of course, the countless calories one had to expend to achieve this goal. By the end of the conversation the unsuspecting mark would have emptied every possible edible item from his car or pack to our benefit. Nick encountered a group of Harvard students on an outing at a shelter and came away with food for three days. We had fried chicken at one road crossing. Cold beer and potato salad at another. Nick was so good at this we turned his name into a verb: We’d speak about “geleskoing” lunch or a “geleskoing” a cold drink on a hot day from day hikers or campers. This odd group of hikers – two aimless wanderers from suburban DC, a youthful ski bum from New England who wanted to sing and play the guitar for a living, and the Michigan Grand-dad shared the remainder of the trek north to Mount Katahdin, cementing a lifelong friendship by sharing cold rains in the Berkshires, warm campfires in the Maine woods, and even a noteworthy short hike with a volunteer camp host in the White Mountains, a young woman who, taking advantage of the sunny day, decided to hike shirtless for a while. I can still see Nick’s eyebrows reaching high on his Midwestern bald pate as she ambled by. The story below I wrote in the year 2000, just after a 20th anniversary reunion hike in Maine organized by Dave, who by that time had written a book about our collective hike (…still in print: As Far As The Eye Can See, by David Brill, Univ. of Tennessee Press). This story was originally published in 2000 in Appalachian Trailway News, a magazine of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. I hope it tells you a little more about this man that we all loved. Gelesko The four of us had last stood here at the base of Katahdin twenty years ago—to the day. I had not seen or spoken to Nick Gelesko or Paul Dillon since we hugged and parted in September 1979. Like many Trail "families," we scattered after Katandin, beginning life stories we were now able to tell to each other for the first time. David Brill and I had rejoined the Trail a time or two together, but we'd let ten years get by since the last walk. A phone call from Tennessee last spring promised an opportunity for a paid trip to Maine. A reunion date was set. Plane reservations were coordinated from Raleigh, Knoxville, Seattle, Nassau, Northampton, and Ft. Myers. A remarkable convergence of schedules brought us all together, joined by fellow '79 A.T. hiker-friends Jim Black and Victor Hoyt. Paul, Dave, Nick and I were celebrating the 20th anniversary of the end of our thru-hike together, drawn back to the same center from which we had spun apart years ago. Nick Gelesko stood in Katahdin Stream Campground, looking up toward the summit, wearing the same khaki shirt he had worn the last time we'd made this climb. Same hat, too. Twenty years of advancing age takes a toll on muscle stamina and often deposits a few pounds in odd places, but, as a group, we had fared passably well. I'd gained about a pound a year; Dillon was the same lean, long-legged hiking machine he was in '79; Brill had apparently not gained any weight except in facial hair; and Gelesko stood trim and tanned, slim and athletic, as I'd remembered him. We had almost run up the Hunt Trail to Katandin's summit twenty years ago, fueled by five months of anticipation and conditioning. Confidence in our muscles and bones we learn from experience. We know our physical limits by reaching them. Exceeding those limits is a leap of faith, a blind dive off a high cliff. Competitive runners win races with their spirit, not their legs. Champion skaters visualize the perfect race... each turn, each stroke of blade on ice. They've won before the gun sounds. I wondered if Gelesko was climbing Katandin in this way now as he looked up at the peak in the glow of early morning. I remember discovering the extraordinary capacity of my own body as I worked my way into shape in the first six weeks of hiking on the A.T. I wrote in my journal then about discovering the "wonders of the lower leg," as somehow my body learned to compensate for fatigue in my quadriceps with greater strength in my calf muscles. Fatigue on the longest climbs means different parts of the body take over, one at a time, shouldering the load, until all that is left to pull you up the final climb to the top is your soul. All else is spent. In early morning, we set off from Katandin Stream, Dave, Paul, and Victor moved swiftly up the face of the mountain, while Jim, Nick and I walked more slowly and steadily onto the great granite slab. In the middle of the first substantial climb, Nick began to slow. His rest stops became more frequent. His jokes became fewer. His strong legs pushed up the mountain just ahead of me, but he struggled over the rock and was clearly fatigued as we emerged from the forest onto the face of the mountain, ready for the steepest part of the climb up to the plateau. In 1979, Nick had met his wife in Shenandoah National Park and hiked with her, his pace slowing to hers, and he'd fallen far behind us. He’d followed our progress in the Trail registers, hiking twenty-five miles a day to our twenty. After almost a month of this, he caught up with us at the Bear Mountain Bridge over the Hudson River. I was not about to leave him again. With a timely push from behind or a hand from above, Nick moved up the steepest part of the climb to the plateau. Open and clear on a beautiful day, the summit appeared close at hand across what appeared a relatively gentle slope to the top. Nick was clearly fatigued by this time, and we were actually more than a mile away, about six hundred feet below the summit. Whatever solace Nick took from the gentler slope was offset by the thinner air and his weakening muscles. I could see in his eyes that the final hundred vertical feet might defeat him. His breath was labored. His pace slowed even further. He was muttering to himself. We stopped. He planted his stick. He looked at the top, looked back at me, and set off, soul alone carrying him the rest of the way. It was late in the day for arrival at the summit of Katahdin – after noon. A large crowd of thru-hikers and others was preparing to descend. One person began to clap, and then all applauded for Nick as he stepped unsteadily atop the final rock. Dave, Paul, Nick and I posed for a photo once again on the summit of the Greatest Mountain. This time, only Nick had an extraordinary achievement to celebrate. As I write this I close my eyes and see the look of supreme happiness on the face of this man, in his black beret and khaki shirt, who, in 1979, traversed the A. T. with three companions less than half his age. He had emerged from surgery on his carotid artery just a few weeks before our reunion hike. At age 79, Nick Gelesko became my hero, again. At home, I try to do a good bit of hiking, a little running, some basketball. Sometimes when I challenge myself I am painfully aware of approaching middle age. The next time I find my body failing under the strain of a steep climb or an athletic competition, I won’t be visualizing the perfect race. I’ll be thinking of a skinny guy in a khaki shirt and beret smiling broadly, leaning on his hiking staff with the rocky ground falling away from him on all sides, blue sky behind. I’ll be hoping just a little of Gelesko’s soul will pull me up and over the top, too.

2 Comments

10/25/2019 06:33:46 am

I think I mentioned earlier that we need to practice entertaining only happy thoughts. If you have to allow negative ideas or things you won't be able to say in the face of the person in front of you, you better shove that thought away and replace it with good ones instead. It takes discipline and practice. They say if you don't have anything good to say, then don't talk anymore. I say it's better if you stop thinking about bad things altogether. If you lose your guard, you can be honest but still exclusively talking about positive things.

Reply

12/2/2019 06:30:53 am

I also have bills to pay. It seems we never run out of such things. I just woke up one day and I realise I now share the same problems my parents had for the longest time. The need to make money to pay the government more money than they deserve. I don't mean to sound entitled but I can't help but not see any reason why there is a need for them to collect from the working class all the time. It should be able to make money on its own.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorDaniel Howe lives in Raleigh, NC. He's interested in a lot of things so this blog is all over the place. Archives

May 2018

Categories |

City Planning / Public Process

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed