After a year’s hiatus I have picked up the blog again, because a lot has changed in the last year. I admit that I have been discouraged during this time – about what it means, now, to be an American, about where the Parks fall in people’s sense of what’s important, about what our priorities seem to be today. What I have always loved about us here on this continent is our idealism. The genesis of the National Park movement from its beginning is the belief that we are going to get better at this – that the values we hold will carry us forward if we pay enough attention to doing good for the most people, being fair, assuming the best about others and not forgetting our mistakes so that we do our best to assure we don’t make them again. The response to this way of thinking was to start setting aside places that remind us of this so that the early Americans’ children could see them and know about the people and natural world that preceded them, and that they can, in turn, mirror that experience in protecting the important lessons and places of their time here so their own children can benefit. So, the news that we are trying to un-protect some National Park lands that we have previously set aside seems to fly in the face of this noble idealism that so characterizes what I think of as my Americanism. Do we really believe that our future is so short that we sacrifice our antiquities, our landscape heritage, our future, for the sake of interests who are intent on exploiting resources on (or under) the land for short-term financial benefit for a few? If we really believe in a long-term future for this country, based on idealistic values that we established two and a half centuries ago, why are we forgetting about “America’s Best Idea” – the idea that the documentation and preservation of our history, culture and our iconic landscapes needs to be protected from short-term thinking and short-run benefit for a few. Has our sense of ourselves as an American community fallen prey to the individualistic sense of “live for today” to maximize personal wealth and power? Have we given up on the future, and on ourselves as an American community? Even as we hear much news on the national level about a swing away from community-think and future-think, I am encouraged by my work with the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, and particularly the ATC’s engagement with a cadre of “Trail Communities”, local governments and civic groups in the Appalachian region surrounding the Trail – a program that provides a testimony to big thinking in the long term. As traditional rural economies shrink or disappear altogether, these communities – most of which are in poor counties in remote locations – have embraced the Trail and its visitors as their ticket to the future. The location of a 2100-mile system of connected open space within a half-day’s drive of 2/3 of the nation’s population draws millions from the major metro areas near the trail, even as their own natural spaces shrink with urban growth. People from Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Raleigh, Charlotte, Knoxville and Atlanta flock to the mountain ridges and to the Trail that provides access to them, and the Trail Communities along this corridor are embracing their relationship with the Trail as economic development, and preservation of the lifestyle these small towns have established. Places like Damascus, Virginia, and Millinocket Maine have seen their traditional local economies shattered by changing global economies, only to rebound as centers of access to nature – with bicyclists, hikers, youth groups and families supporting hotels, outfitters, restaurants and, ultimately, tax base. The ATC is embracing its role in bringing these communities together to share best practices, help support the preservation of the natural and settled landscape surrounding the Trail, and provide the volunteer base that essentially runs this National Park Service unit under contract. It is a remarkable system, started by Benton MacKaye, a city planner, in 1921 with his landmark challenge to establish the AT along the East Coast. He saw, using the characteristic American trait of assuming the future will come and we should all benefit, that the East would urbanize and this interconnected system of open land along our Eastern mountain chain would become critical to the millions who live near it. It took 150 years to completely protect the continuous footpath from Georgia to Maine, with no small assistance from the National Park Service and the generous contributions from Federal taxpayers. And now the challenge is to protect the landscape that is viewed from the trail – the forests, farms and fields that speak to an ever-shrinking rural America – an agrarian past that we still hold close in our national consciousness. The AT is the crown jewel of the National Trails System, that also includes the Pacific Crest Trail, the Continental Divide Trail, the Natchez Trace and many other linear experiences of history and landscape across the US. Through partnerships with volunteer organizations like the ATC and the Trail Communities along the Appalachian chain, the NPS manages the entire 2100-mile Trail with a staff of about 10. Like the establishment of the National Parks, MacKaye’s vision is truly a reflection of America’s best thinking, which otherwise seems startlingly lacking in a live-for-today world where we seem to be content to ignore that which would benefit us all in the future in our headlong rush to get ours while we can. This year I received one of my best birthday presents ever, from my son Sam. I now have an America the Beautiful National Park and Federal Recreation Area Lands Pass – my ticket to the lands we have so wisely set aside, from Yosemite to the Everglades, from the Wildlife Habitats of the West to the recreation areas of the South. Now, I really feel like I’m an owner – I’ve got mine, but it’s everybody else’s too. I will end this with one of the best stories we’ve collected in Simon Griffith’s and my travels around the parks. National Park Ranger Gary Bremen addressed a group of new citizens – immigrants – at Biscayne National Park in Florida. In his speech he congratulated them for being new property owners in their adopted country. He got them excited about the Park they are sitting in, and then he told them that they now own it - 23 ½ square feet each. He said that most of them will get water (Biscayne is 95% water), but if they are particularly grumpy or complain too much some of them might get a portion of the bathroom or the parking lot. He also told them they not only own this park, they own 163 square feet of Everglades National Park, just 18 miles away, and 300 square feet of Yellowstone National Park, with its pools of boiling water, geysers and mud pots, its wolves and bears and bison. He told them they all own about 1 1/4 square inches of Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island where so many people just like them had their first view of this country and set foot upon it for the first time. He reminded them that this is ours, collectively AND individually, and the best ideas of generations long passed have resulted in these places being here so we can experience them – live in them for a short while and feel what it feels like to be American. I hope we don’t forget that. I hope we all find new ways to come together and think beyond tomorrow – to our children’s time, when they will set foot on a Trail set aside by their fathers and mothers, and in a desert preserve sacred to those even further removed in time, and remember what’s unique about this society – that we are all in it together and together it represents the best of all of us. View the MyATStory production – Damascus: http://www.appalachiantrail.org/home/conservation/a-t-community-program

1 Comment

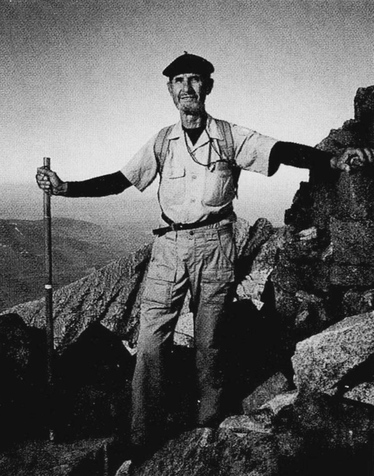

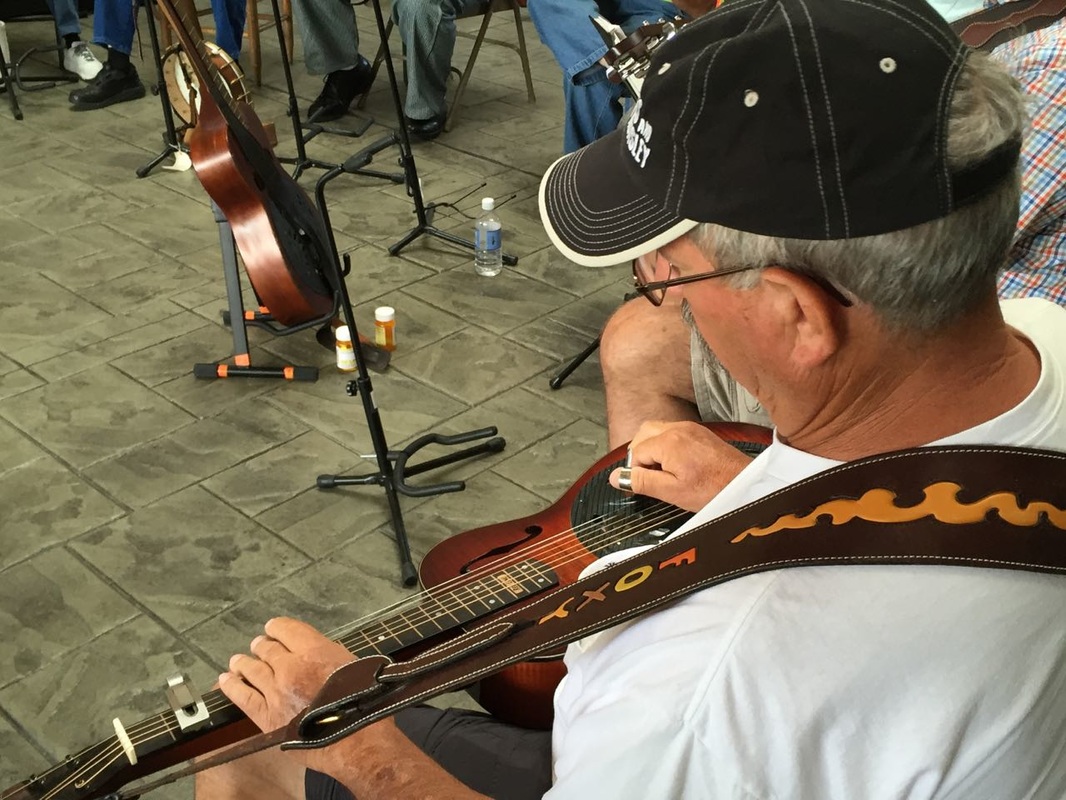

I’ve followed the story of the new administration in Washington, DC, and its initial efforts to recast the public narrative across the bureaucratic board, but most interestingly I have been following a small revolution within the National Park Service and staff upheavals in the areas of diplomacy and intelligence at the national level. And after considering all this for a while I found myself buying a bumper sticker through the altNational Parks Facebook page. Here’s why. When I was young my ideas were more untethered. Like a puppy that finds itself suddenly out of the crate and onto the unlimited expanse of the kitchen floor my ideas would head out enthusiastically in random directions, occasionally stumbling into a snout-plant and periodically circling back to a lap or the crate entrance to ensure that in this freedom I was not entirely unmoored. I recall bringing myself to a point in my enthusiasm as a young person where a quote (attributed, correctly, to me) in a local free publication caught the eye of my employer, whose arm metaphorically thrust up through the floor from the offices below and yanked me downstairs to remind me that perhaps I didn’t know the complete story, and at the very least my narrative did not conform to that of the organization. I was off-message – in a somewhat large and troubling way. I survived that reminder to continue to speak freely, if more discreetly, to my leadership, but I find that my ideas still stray out of the yard now and again. I’ve also understand now more clearly that there are many fine reasons why it is a good practice to allow them to sometimes lie quietly in the sun inside the fence before I start looking for a hole in it. The collective intelligence of a large organization is complex. It is not simple to know enough to speak for the whole while being unaware of the ideas of the parts, and any organization depends not only on good leadership to set the direction and speak this intelligence, but also on the freedom of those at the far reaches of the organization to communicate honestly to leadership. This is best done and most effectively done, I have found, internally – person-to-person, a “crucial conversation” as often termed in the organizational development world, respecting the broadening responsibilities of everyone up the chain to the top, and the challenges that come with existing on those lofty levels. These systems work well when a few simple things are true. There must be respect from above to below, about the work one performs and the knowledge one must have to effectively accomplish even the smallest and most mundane tasks. If this is not true there will be little respect afforded from below to those above. There must be no secrets within the chain of communication. If mysteries exist the novelist in us all fills the vacuum with the story that’s most fun and likely most outrageous. There must be care that people with differing opinions are not marginalized or muzzled, but listened to. Even if the organization does not absorb their narrative, it must be seriously considered and debated at the very least. The AltNPS movement sprung up in late January when the administration issued an order through the Department of the Interior to stop scientists from speaking of or publishing any material on climate science (one of the key resource management issues in the National Park system today) and shut down all social media outlets in the Parks for a wide variety of content. A number of employees, starting with a small group from Badlands National Park on the vanguard of the Twitter storm (some others in the Twitterverse started calling it Badass National Park), decided to resist and spend their off-duty hours outside the crate on the kitchen floor, off-message, defending the work of the Park Service to perform their mission using the best science, arguing that there was no consensus built about this silencing of park staff, and no respect for the scientists closest to the issue within the organization, and being generally critical of the new administration. This list has since expanded to people purportedly representing staff in Arches, Shenandoah, Yosemite, Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, the Blue Ridge Parkway, Everglades, and Great Smoky Mountains National Parks. Well, I found my own ideas about this scurrying about the floor. Yes, clearly it is the right and perhaps even the responsibility for senior leadership in a large organization to set the public agenda, develop a leadership message and expect the ideas of those within the organization to stay in the crate so as not to confuse those outside the organization. And mostly that has held true at the crux of transitioning administrations throughout our national history. It works (except in this case) because the organizations follow the unwritten rules of internal dynamics – the seniors respect the knowledge and ideas of those at the far reaches of the organization, messaging is distanced from managing and dissent is channeled internally where it is tended and massaged before a decision is made. There are no mysteries – the reason a new narrative exists is clear and clearly passed down the line. The only thing that is clear in this case is that the message passed down from the new administration is not. Some things are off limits (“national policy” issues like climate change, which to me seems like a scientific issue), and others are not (safety, information, etc.). Little consultation seems to have taken place down the line to staff in the parks before the social media orders were handed down. The scientists whose work has been to try to get ahead of threats to the parks in the future found their work censored without any internal discussion. What is going to happen to this effort to manage the parks in a way “as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations” (1916 Organic Act creating the National Park Service) if the very experts we hire to figure out how to do this are not listened to? It’s a mystery and you know what people do when faced with a mystery… Although my inclination is to let my ideas bask a little in the sun within the fence for a while, I find myself rooting just a little for the AltNPS puppies out there on the kitchen floor. It’s not a model that is sustainable in any organization, but I’m interested to see how this little bit of chaos might change the outcome. In time my hopes are that the level of respect up and down returns and the suddenness of activity at the top of the organization moderates a little so there is less need for rangers to speak on social media on their own time and for diplomats to publicly challenge their new superiors before they are even on the job. We have thousands of outstanding rangers across the political spectrum dedicating their lives to the parks, monuments and historic sites, as well as a knowledgeable and experienced team of international experts in the foreign service. Any wise leader understands that you don’t encourage the dogs to stay in the fence by shooting at them or tying them to a tree. Make sure they feel they are still part of the pack. Respect them and listen before acting and there’ll be a lot less howling.  When Simon and I visited Gayle Hazelwood in Atlanta last summer, we had no idea what to expect. My good friend Don Barger had highly recommended we hunt Gayle down to interview her for our book. Don is the Southeast Regional Director of the National Park Conservation Association, and he said Gayle was the best interpreter at Martin Luther King, Jr. Historic Site he'd ever known. He also said that she had, at one time, the best business card in the Park Service: "Superintendent of Jazz". This was her title when she was Superintendent at New Orleans Jazz National Historic Park in Louisiana. Nothing could have prepared us for the dervish that we met in Ms. Hazelwood. Her energy is absolutely infectious, and the three of us became friends almost immediately. Gayle is not your average ranger. She's African-American. She's gay. She's a woman. And if that's not enough, she's 30% native American. She's also an urban park ranger - trying to engage a generation of youth whose experience of our country's history and heritage is a lot more concrete and cacophony than it is forest and waterfall. That is a formidable diversity package. Some 80% of this country's population lives in a "metropolitan area". We are an urban culture, becoming more so every day. The National Park constituency in this country is overwhelmingly white, and aging, unlike our general population which is trending younger and more colorful. To their credit, the National Park Service leadership is determined to turn the battleship and bring more relevance of its special landscapes to those for whom the end of the subway line might as well be the end of the world. Dozens of parks close to urban concentrations (Gateway National Recreation area in New York and New Jersey, Cuyahoga Valley in Cleveland, Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area in Atlanta, etc.) have been established, and the Park Service has set lofty goals for a new series of water trails, historic sites and urban recreation areas in its strategic plan for the second 100 years of its existence. The Park Service has also instituted a series of programs and partnerships intended to organize tours to the classic breathtaking landscapes of the Park System specifically for under-served groups in our society - Latinos, Asians, African-Americans, the urban poor. My daughter Linnea and her youth group friends walked the Freedom Trail in Boston this past summer - an urban experience that, through a thin line of contrasting bricks in the sidewalk pavement, draws you creatively through a number of historic places, a classic urban National Park Service creation - less a park than an experience. Still, the story this experience tells is the story of people who look like me, not like Gayle Hazelwood. The National Park Service challenge is to build a portfolio of new places that tell the stories of the subsets of humanity that have blended together into an American experience, places like the recently-designated Stonewall National Monument, or the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site - where we met Gayle. We middle-class suburban kids grew up on Yellowstone and the Grand Canyon, and it came as a surprise to me to find that there are 28 National Park Service sites focused on the history of the African-American experience in the United States, ranging from Little Rock Central High School in Arkansas, to the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site, to New Orleans Jazz National Historic Park and Jean Lafitte National Historic Park and Preserve, which we are to visit in just a couple of weeks when we travel to New Orleans to make a presentation to the national conference of the American Society of Landscape Architects. Gayle's story is remarkable in a number of ways, but the part I like the best is that music weaves through it all the way from her childhood in Ohio to her home in Atlanta, where she now serves as the Director of the National Park Service Urban Agenda. All roads seem to lead through New Orleans, though, and that's why I am so excited to be there soon amidst the smells of white pepper and onion, and within earshot of the finest musicians on the planet. To learn more about Gayle, read her story.  Gayle Hazelwood, Director of the NPS Urban Agenda. She's shown with youth in Atlanta at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Historic Site. They are part of the Greening Youth Foundation, a National Park Service partner. Photo by Simon Griffiths Gayle Hazelwood, Director of the NPS Urban Agenda. She's shown with youth in Atlanta at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Historic Site. They are part of the Greening Youth Foundation, a National Park Service partner. Photo by Simon Griffiths The Centennial birthday of the National Park Service is nine days away as I write this, and I’m celebrating in a few ways large and small. This morning I walked Luna the dog down around Roanoke Park, a block from my home. I live in a comfortable neighborhood with small yards and narrow streets. Everyone has at least some landscape to enjoy within the boundaries of their own lot, but the neighborhood would not be the same without the park. It’s a small place, essentially an old creek bed with the creek sleeping in a pipe beneath the small valley. On an average day the playground is swarmed with toddlers and parents, an afternoon pickup basketball game entertains a few sweaty young men, a dog chases a Frisbee in the sunny field and a couple of teenagers hang out at the picnic shelter. They all feel some sense of ownership of this place and nobody’s trespassing. It’s public - a landscape where people feel some sense of ownership and yet are comfortable being together with strangers. How many places do we have like that in our world? My neighbors and I pay taxes, and a portion of that money helps compensate a couple of hard-working guys who come by with ride-on mowers on a hot day to mow the grass every week or so, and pays for the volleyball net the neighborhood requested to support our Sunday afternoon pickup volleyball tradition. What I love about this park tradition is that it is ours – plural. We all feel equally entitled to use it, and we all ante up a small contribution to care for it. Frederick Law Olmsted, famous with his partner Calvert Vaux for the design of our first signature urban park, Central Park in New York, called for his park to be “the locale of class reconciliation”. From the beginning, parks in this country were intended to break down the barriers of class and ethnicity to bring people together, rich and poor. This has been more and more on my mind as our city embarks on an ambitious effort to turn a closed mental hospital campus into a “destination park”. It is a rare opportunity to craft a park, a big one, in the center of the city and the process of this is starting out in the spirit of park-making, under a big tent. 100 years ago, when the National Parks were young, they were also remote and accessible only by very few people with means, traveling by train from eastern cities to the grand western landscapes that had been preserved at that point. Much of the first 100 years have been spent encouraging white, middle class people to visit the parks and support the system and its expansion and in that we have been very successful. The “See the USA in your Chevrolet” marketing campaign in the 1950’s and 1960’s was not aimed at black people riding the subway. It is rare to find a white, middle-class Baby Boomer whose personal history does not include some seminal moment spent as a child in a National Park. That is not true of most people of color and people of lower incomes who live in cities. Today only about one in five visitors to National Parks are non-white, and one in ten are Hispanic, even as the non-white and Hispanic proportion of the population as a whole exceeds 40%. As our society becomes more urban and less white, visitation in the parks more represents the America of forty years ago than it does that of today. Gayle Hazelwood, one of the rangers profiled in our book and the director of the National Park Service’s Urban Agenda, reminds us that for many urban kids mountains may look nice from a distance, but represent for them dangerous wildlife, hungry mosquitoes and a disconnected isolation that is not in any way appealing to someone who has never been further from home than the last stop on the bus line. For many of these urban youth a uniform and a badge represents something to be feared, even if accompanied by a flat hat. Gayle, who is herself African-American, points out the efforts that have been made by the National Park Service to make the parks relevant to an urban population not simply by trying harder to attract urban and non-white populations to the traditional parks (which they have), but by bringing parks to urban settings. There are now National Park units in 40 of the 50 most populous urban areas in the country. And the Park Service has challenged itself to tell the story of our collective history written in landscapes that are local and relevant to our urban and younger population, by partnering with local YMCAs, parks and recreation departments and non-profits to engage urban youth in experiences in the National Park units in their own community. This is not just an urban issue. Park Ranger Matt Hudson, also the subject of a book profile, helped launch “National Park in Your Back Yard”, a program in rural Morgan County Tennessee that allows every 6th grader in the county an opportunity for a full day field trip rock-climbing and paddling at the Obed Wild and Scenic River. A teacher involved with the program in this remote, low-income county estimated without National Park In Your Back Yard two out of every three children growing up in Morgan County would never set foot in this National Park less than 25 minutes from even the most remote part of the county. What is important about parks and the tradition of setting aside common landscape is this notion of common ownership. I feel like Roanoke Park is mine, in some small way. I feel it is my right and privilege to shoot baskets there when I take the notion, to throw a ball for Luna, to watch others in the park, and to watch out for them, too. As the scale of a park and the distance from our home place expands, it is easy for this sense of ownership to diffuse, for the landscape to become disconnected from us and become someone else’s – the “government’s” perhaps, as if the government was not put in place, through the ballot box, by us. This is the critical mission of engagement, and as my city launches into an effort to create its “destination” park we will be successful to the extent that this large, central landscape somehow generates a sense of ownership, a sense of commonality, across our increasingly diverse population. In a time when we seem driven into ideological or socio-economic camps or into a defiant notion of individualism, this is a chance to remember why we started all this…not just the parks movement but the whole notion of a democratic republic. It will not be like Central Park in many ways, but I hope that as we build this new park we will hearken to Olmsted’s call and find a way to make it a landscape both color-blind and classless. When Simon and I visited National Park ranger Gary Bremen at Biscayne National Park in Florida and listened to him address a group of new citizens, immigrants who were about to take the citizenship oath, he told them they were about to become owners of some pretty spectacular real estate - 23 ½ square feet each of Biscayne National Park. He said that most of them will get water (Biscayne is 95% water), but if they are particularly grumpy or complain too much some of them might get a portion of the bathroom or the parking lot. He also told them they not only own this park, they own 163 square feet of Everglades National Park, just 18 miles away, and 300 square feet of Yellowstone National Park, with its pools of boiling water, geysers and mud pots, its wolves and bears and bison. He tells them they all own about 1 1/4 square inches of Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island where so many people just like them had their first view of this country and set foot upon it for the first time. This notion of ownership of and responsibility for our common landscape, our common heritage, is what parks are all about and it is what we are celebrating at the Centennial this August 25th. Simon and I will be traveling at the end of August to Mt. Rainier National Park, where I own 32.3 square feet, and to Olympic National Park, where my stake is 126.1 square feet. I couldn’t be more proud. I hope I don't get the bathrooms. In my ownership role, I hope to do some little part to fulfill the stated purpose of the Park Service, as Olmsted’s son Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. wrote in the 1916 Organic Act that created the National Park Service, “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wild life therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.” Future generations will not look like me, so it will be important to all of us to look forward as much as we look back on this birthday. Remember this on August 25th whether you spend the day visiting Yosemite or simply walking the dog in your neighborhood pocket park. It’s yours to own and share…with everyone. Take the opportunity to say hello to someone you don’t know in a park, and say thank you to those who helped start this grand tradition and to those who keep the parks open and the grass mowed for us every day. For more information about our book, RANGERS, Personal Stories of National Park Rangers and the Landscapes They Preserve and Protect, click here.  Ralph Stanley, image courtesy The Bluegrass Situation Ralph Stanley, image courtesy The Bluegrass Situation Ralph Stanley died Thursday at the age of 89, just a few days after I returned from a visit to the National Park Service’s Blue Ridge Music Center near Galax, Virginia. The Music Center exists to celebrate the music that Ralph Stanley and his brother Carter helped popularize – a folk tradition that spans at least 7 generations here in this country, and even further back in the Gaelic and Scots ballad traditions in the British Islands. The Stanley Brothers, and their southwestern Virginia neighbors A. P. Carter and his musical family, took “hillbilly” music to the national stage beginning in the 1940’s when Ralph and Carter formed a band, the Stanley Brothers and the Clinch Mountain Boys, and began performing in and around Bristol VA and Johnson City, TN. Ralph Stanley never used the term “bluegrass” to describe his music. Kentucky native Bill Monroe and his band the Bluegrass Boys popularized the term (a sound which, ironically, is often credited to NC banjo player Earl Scruggs). Stanley is perhaps best remembered for the “high, lonesome” sound his clear tenor emphasized, a sound that rings clear in mountain hollows from Madison County, NC near Asheville north to Bristol and Kingsport in Tennessee, and east to Galax, Virginia and Mount Airy, North Carolina. It is the musical theme of a hard life in a beautiful place. The title of Stanley’s 2009 autobiography, “Man of Constant Sorrow” says a lot about the bittersweet world of the Southern Appalachian mountains, a place of breathtaking natural beauty, strong families, tragedy and struggle – the perfect mash for a rich world of art in music and craft. Last year on a long-distance bike ride in southwestern Virginia, not far from Stanley’s original home on Big Spraddle Branch, I stopped at the A. P Carter homestead, home of the famous Carter Family, listened to a string band perform on the porch, and even sat in Johnny Cash’s easy chair (Cash married June Carter, daughter of Maybelle Carter and niece of A.P. Carter). I’ve been playing this music for 25 years and the experience of being at the Carter home, and riding through the mountain valleys that inspired their music gave me chills. Similarly, last week at the Music Center on the Blue Ridge Parkway, I was able to listen to Galax, VA native Dori Freeman warm the crowd up for the Steep Canyon Rangers, and Freeman’s voice was once again rich with pain and love and anger, notes in her original songs inflecting up or breaking an octave down – the same plaintive call from the hills I remember from listening to friends sing in my time in Madison County. There is a hardness here, a life of disappointment and struggle and love and family and nature all wrapped up together and aching to emerge in song from so many who have lived in this land. Basically everyone up here is a musician. Every day at the Music Center people gather in the breezeway (in good weather) or in the luthier’s shop (in bad) to unpack guitars and mandolins and dobros and dulcimers and fiddles and banjos and basses from well-work cases to crank through a few hours of “Are You Washed In The Blood?”, “Shady Grove”, “Cotton-Eyed Joe”, “Cluck Old Hen”, and a few hundred other songs that everyone in the circle can play along with once the leader announces the key. Those that don’t play, sing. And they know all the words. They are young and old – sometimes very old - and sometimes very young. I have a friend here in Raleigh whose 13-year-old daughter plays the fiddle in the traditional style and plays rings around most people three times her age. This is back-porch music, music where you need to set aside a room to put the instrument cases when you hold a pot luck, music that works as well in a capella harmony out front of the grocery store as it does with a full string band. Mountains and hollows, branches (creeks), balds and coves…this is the landscape that raised Tommy Jarrell (he lived in Round Peak – about 15 miles from the Music Center), and Doc Watson (his home in Deep Gap is about 40 miles down the Parkway). In the springtime they sing about the “Wildwood Flower”, in the winter “The Fields Have Turned Brown”. There are songs about hard work (“Coal Miner’s Blues”), and faith (“Little White Church”), about liquor (“Mountain Dew”) and love (“Gold Watch and Chain”), and about murder (“Little Omie Wise”, “Tom Dooley”) and death (“Will the Circle Be Unbroken”, “Bury Me Beneath the Willow”). Stanley is part of a disappearing generation. Doc Watson passed on in 2013. Earl Scruggs died in 2012. Tommy Jarrell left us in 1985. The music continues in hollows and hills surrounding the Blue Ridge Parkway…and among millennials. Someone on the radio the other day said that it’s hard to find new popular music that is not categorized as “Americana”. Think Avett Brothers, Allison Krause, Nickel Creek, The Head and The Heart. Bluegrass as a genre is still popular, and increasingly so around here. The International Bluegrass Music Association annual meeting and festival here in Raleigh drew over 180,000 people in 2014. I cannot remember a better live music concert, ever, than the one Canton, NC’s Balsam Range performed on the free stage on Hargett Street that year. Now distant from its founding traditions, country music covers the earth but it’s important to remember where the Nashville sound started – in the hills of home in the shadow of Clinch Mountain, somewhere around Big Spraddle Branch where Ralph and Carter Stanley started playing the old tunes they heard from their family and friends. Ralph Stanley had been famous among lovers of this music for decades before he reached a new audience in 2000 on the soundtrack of the movie “O Brother Where Art Thou” with his haunting a capella rendition of “O Death”, the story of an old man bargaining with death to “spare me over for another year.” He lost the bargain yesterday, but not before his high, lonesome sound worked its way into my head and that of countless others, forever. My latest sun is sinking fast, my race is nearly run My strongest trials now are past, my triumph has begun Oh come Angel Band, come and around me stand Oh bear me away on your snow white wings to my immortal home Oh bear me away on your snow white wings to my immortal home From “Angel Band” – traditional Appalachian Gospel tune Click below to view a live performance of "O, Death" from 2008:  Nick Gelesko on Mount Katahdin in 1999 at age 79. Scanned photo of an image by photographer Chris Rainier for National Geographic Traveler magazine. Nick Gelesko on Mount Katahdin in 1999 at age 79. Scanned photo of an image by photographer Chris Rainier for National Geographic Traveler magazine. Nicholas Gelesko died on May 27. He would have been 95 years old in November of this year. He was a skinny old man with a Michigan accent who used to love to play tennis at his condo in Florida that he shared with his bride, Gwen. I first saw Nick when he wandered into a shelter site on the Appalachian Trail 38 years ago with a floppy white hat on his bald head, wearing a khaki shirt with epaulets and a shoulder patch (Appalachian Trail – Maine to Georgia), underneath a red rain jacket. He immediately sat down and started asking us about where we were from and about our names and families. And then he started telling stories in his characteristic Michigander accent about the Navy, and his long career as an engineer, about his several children and about so many other things that I have forgotten most of them, but I can still see him smiling and I can still hear him laugh at his own jokes. He was 58 at that time - already an old man in the reckoning of a 23-year old, but sturdy and athletic. Nick had recently retired from Westinghouse, where he worked as an engineer and, like many of us he was on the Trail in search of a new fulcrum point in his life. Off and on over the first two months on the A. T. my hiking buddy David Brill and I would regularly come across Nick and the group of people with whom he was hiking. It’s the culture of the Trail to be part of an interwoven social network of small groups, connected to the doings of others by trail registers located in each shelter. Long-distance hikers would sign in and note the day’s events, providing a collective diary of the community of walkers headed north. An extra day in a town would allow a group behind you to catch up. A particularly long day’s hike might allow you to overtake another group at a shelter whom you’d not seen in weeks. It was a series of departures and reunions, the cast thinning as the play wove on. Injuries and fatigue, internal demons and bad equipment took their toll, and at the psychological halfway point of the trail in Harper’s Ferry, only the durable and determined were left, generally a fraction of those who set out on Springer Mountain in Georgia for Maine. During his journey north through the Southern Appalachians, Nick’s wife Gwen had traveled from Michigan to hike with him for two weeks through the Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, and his pace slowed to match hers. During the two weeks with her he fell far behind everyone who was part of his social network on the Trail. After she returned home upon completing their hike together, Nick began following my small group in the trail registers as he worked his way north. We had picked up a third member of our entourage by then. Paul Dillon was a tennis-and-ski bum from New Hampshire, long of leg and hair and younger than either of the two of us. We came across him early in our time in Pennsylvania and the connection stuck. Paul would stand on Katahdin with us that fall. The three of us were hiking through the Mid-Atlantic states by that time, and were traversing Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York in long strides, often walking in excess of twenty miles each day. For every twenty miles we’d hike, Nick would hike twenty-five in an attempt to catch up to us. This he did for 300 miles until he caught us on Bear Mountain near the Hudson River. We walked every step of the rest of the way together, the “Michigan Grand-dad” (his trail name) earning his keep by finding dozens of interesting ways to talk people out of their food. Any visitor to the Trail who happened to ask Nick about his hike would inevitably hear a poignant story about the endless steepness of the mountains, his advancing age and of course, the countless calories one had to expend to achieve this goal. By the end of the conversation the unsuspecting mark would have emptied every possible edible item from his car or pack to our benefit. Nick encountered a group of Harvard students on an outing at a shelter and came away with food for three days. We had fried chicken at one road crossing. Cold beer and potato salad at another. Nick was so good at this we turned his name into a verb: We’d speak about “geleskoing” lunch or a “geleskoing” a cold drink on a hot day from day hikers or campers. This odd group of hikers – two aimless wanderers from suburban DC, a youthful ski bum from New England who wanted to sing and play the guitar for a living, and the Michigan Grand-dad shared the remainder of the trek north to Mount Katahdin, cementing a lifelong friendship by sharing cold rains in the Berkshires, warm campfires in the Maine woods, and even a noteworthy short hike with a volunteer camp host in the White Mountains, a young woman who, taking advantage of the sunny day, decided to hike shirtless for a while. I can still see Nick’s eyebrows reaching high on his Midwestern bald pate as she ambled by. The story below I wrote in the year 2000, just after a 20th anniversary reunion hike in Maine organized by Dave, who by that time had written a book about our collective hike (…still in print: As Far As The Eye Can See, by David Brill, Univ. of Tennessee Press). This story was originally published in 2000 in Appalachian Trailway News, a magazine of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. I hope it tells you a little more about this man that we all loved. Gelesko The four of us had last stood here at the base of Katahdin twenty years ago—to the day. I had not seen or spoken to Nick Gelesko or Paul Dillon since we hugged and parted in September 1979. Like many Trail "families," we scattered after Katandin, beginning life stories we were now able to tell to each other for the first time. David Brill and I had rejoined the Trail a time or two together, but we'd let ten years get by since the last walk. A phone call from Tennessee last spring promised an opportunity for a paid trip to Maine. A reunion date was set. Plane reservations were coordinated from Raleigh, Knoxville, Seattle, Nassau, Northampton, and Ft. Myers. A remarkable convergence of schedules brought us all together, joined by fellow '79 A.T. hiker-friends Jim Black and Victor Hoyt. Paul, Dave, Nick and I were celebrating the 20th anniversary of the end of our thru-hike together, drawn back to the same center from which we had spun apart years ago. Nick Gelesko stood in Katahdin Stream Campground, looking up toward the summit, wearing the same khaki shirt he had worn the last time we'd made this climb. Same hat, too. Twenty years of advancing age takes a toll on muscle stamina and often deposits a few pounds in odd places, but, as a group, we had fared passably well. I'd gained about a pound a year; Dillon was the same lean, long-legged hiking machine he was in '79; Brill had apparently not gained any weight except in facial hair; and Gelesko stood trim and tanned, slim and athletic, as I'd remembered him. We had almost run up the Hunt Trail to Katandin's summit twenty years ago, fueled by five months of anticipation and conditioning. Confidence in our muscles and bones we learn from experience. We know our physical limits by reaching them. Exceeding those limits is a leap of faith, a blind dive off a high cliff. Competitive runners win races with their spirit, not their legs. Champion skaters visualize the perfect race... each turn, each stroke of blade on ice. They've won before the gun sounds. I wondered if Gelesko was climbing Katandin in this way now as he looked up at the peak in the glow of early morning. I remember discovering the extraordinary capacity of my own body as I worked my way into shape in the first six weeks of hiking on the A.T. I wrote in my journal then about discovering the "wonders of the lower leg," as somehow my body learned to compensate for fatigue in my quadriceps with greater strength in my calf muscles. Fatigue on the longest climbs means different parts of the body take over, one at a time, shouldering the load, until all that is left to pull you up the final climb to the top is your soul. All else is spent. In early morning, we set off from Katandin Stream, Dave, Paul, and Victor moved swiftly up the face of the mountain, while Jim, Nick and I walked more slowly and steadily onto the great granite slab. In the middle of the first substantial climb, Nick began to slow. His rest stops became more frequent. His jokes became fewer. His strong legs pushed up the mountain just ahead of me, but he struggled over the rock and was clearly fatigued as we emerged from the forest onto the face of the mountain, ready for the steepest part of the climb up to the plateau. In 1979, Nick had met his wife in Shenandoah National Park and hiked with her, his pace slowing to hers, and he'd fallen far behind us. He’d followed our progress in the Trail registers, hiking twenty-five miles a day to our twenty. After almost a month of this, he caught up with us at the Bear Mountain Bridge over the Hudson River. I was not about to leave him again. With a timely push from behind or a hand from above, Nick moved up the steepest part of the climb to the plateau. Open and clear on a beautiful day, the summit appeared close at hand across what appeared a relatively gentle slope to the top. Nick was clearly fatigued by this time, and we were actually more than a mile away, about six hundred feet below the summit. Whatever solace Nick took from the gentler slope was offset by the thinner air and his weakening muscles. I could see in his eyes that the final hundred vertical feet might defeat him. His breath was labored. His pace slowed even further. He was muttering to himself. We stopped. He planted his stick. He looked at the top, looked back at me, and set off, soul alone carrying him the rest of the way. It was late in the day for arrival at the summit of Katahdin – after noon. A large crowd of thru-hikers and others was preparing to descend. One person began to clap, and then all applauded for Nick as he stepped unsteadily atop the final rock. Dave, Paul, Nick and I posed for a photo once again on the summit of the Greatest Mountain. This time, only Nick had an extraordinary achievement to celebrate. As I write this I close my eyes and see the look of supreme happiness on the face of this man, in his black beret and khaki shirt, who, in 1979, traversed the A. T. with three companions less than half his age. He had emerged from surgery on his carotid artery just a few weeks before our reunion hike. At age 79, Nick Gelesko became my hero, again. At home, I try to do a good bit of hiking, a little running, some basketball. Sometimes when I challenge myself I am painfully aware of approaching middle age. The next time I find my body failing under the strain of a steep climb or an athletic competition, I won’t be visualizing the perfect race. I’ll be thinking of a skinny guy in a khaki shirt and beret smiling broadly, leaning on his hiking staff with the rocky ground falling away from him on all sides, blue sky behind. I’ll be hoping just a little of Gelesko’s soul will pull me up and over the top, too. For a while I lived in the mountains. I took a long hike across several mountain ranges with my excellent friend David Brill for 5 months as we walked from north Georgia to Maine, and then I moved to western North Carolina – to Madison County, on the Tennessee line north and west of Asheville.