|

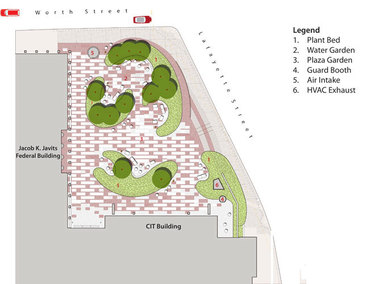

The idea that there should be outdoor public space – a park - accessible to all did not begin with Frederick Law Olmsted and the Central Park experiment in New York, but the popularity of such places certainly followed in his wake. After Central Park, cities across the nation started jumping over themselves in a headlong rush to build parks – Brooklyn, Buffalo, Kansas City, St. Louis, Chicago, Boston. The City Beautiful movement spawned by the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1893 created a related but different movement to establish more formal outdoor open space, generally terminated by a white neo-classical building or monument intended to inspire a sense of grandeur and patriotism (the Mall in Washington, DC stands as the best example of the City Beautiful movement applied to outdoor public space). At the same time Olmsted, Theodore Roosevelt and others worked in support of a larger and grander vision even than that – the preservation of massive iconic Western landscapes in the form of parks not just for people in cities but for an entire nation – the National Parks. Cities since Olmsted’s day have been regularly punctuated by plazas, pocket parks, greens and squares with a variety of intentions, very few of which are not directly associated with the intent of building a “gathering space”. Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, his partner in the design for Central Park, were Progressive-era big thinkers. Their idea for the Park was, as Olmsted puts it “the locale of class reconciliation”. It was purposefully designed to allow the wealthy in their carriages to cross paths with the strolling workers and their families as they all enjoyed the illusion of nature in its pure form as created by Olmsted and Vaux’s masterful re-design of a rocky wasteland. It’s important to remember that at that time, the gap between the wealthy “one-percent” (they were called “robber barons” back then) and the working class in terms of their relative proportion of the wealth of the nation was very similar to what we are experiencing now, so this egalitarian idea was intended to directly address this perceived gap. William H. Whyte, a social researcher working in the 1970’s, shed a considerable light on the inadequacies of public spaces to respond to this objective, primarily by pointing out how public places built during the heyday of the mid-20th-century Modernist movement failed to address basic human desires and characteristics. Whyte, utilizing time-lapse photography, came to realize that people avoided these expensive designer-created open spaces unless they met a few simple criteria: Don’t put people in a wide-open windswept place and expect them to stay long. Give people options for seating – let them arrange the seating as they would like. People love water – give them access to it. Dense vegetation doesn't make visitors feel cozy - it makes them feel worried. And perhaps most important – food attracts people! One of my favorite urban philosophers, Grady Clay, who wrote for years about what he perceived of city space around him as he traveled, pointed out in an essay entitled “What Makes A Good Square Good?” that the answer to this question is, in a single word, action. Clay (and Whyte as well) makes the point that people are attracted to places where they can look at other people and be seen themselves. To the extent that designers build in more opportunities for people to be part of the show, and at the same time be part of the audience, the more successful and loved a public space will be. Hence a sunken plaza with a restaurant in it might make the people in the restaurant part of the show, but they can’t see out and fail to be part of the audience for what is going on around them. Designers for a long time followed Olmsted’s lead and tried to re-create the English landscape of meadows and trees in park after park across the country, but since the middle of the 20th century the urban public open space has been the subject of a more intensive effort to find the design palette that works as both a work of landscape art and as a functional “locale of class reconciliation”. We’ve not been entirely successful. Whyte’s withering critique of high mid-century open space design pointed out that the best places were not always the most striking from an architectural standpoint, and the most sculptural were often the worst from a human standpoint. Take for example the continuing saga of Jacob Javits Federal Building Plaza in New York City.  The complex was built in 1969 with the Plaza added as a zoning amenity that allowed greater density on the rest of the site, the same sort of density-bonus zoning that created so many of Whyte’s NYC examples of windswept, vacant spaces. Ada Louise Huxtable, Architectural critic for the New York Times when the Javits Center was built, referred to the complex as, “one of the most monumentally mediocre Federal buildings in history” (as quoted in NYC Architecture). The outdoor space was notably empty most of the time and environmentally unpleasant. In 1979 the National Endowment for the Arts funded a project to introduce sculpture to public spaces, and commissioned sculptor Richard Serra to create a work for Javits Plaza. His sculpture “Tilted Arc”, a long wall of Cor-Ten steel, was introduced to the plaza and immediately drew opposition. A review board recommended relocation, which the artist objected to, and ultimately the sculpture was simply removed in 1989. The waterproofing began failing beneath the plaza in 1992 (it was built atop a parking structure), and so Martha Schwartz Partners was commissioned to redesign the plaza into a work of high art that, upon its completion, won a 1997 American Society of Landscape Architects Honor Award. Still, people avoided the space. Because the waterproofing was again failing beneath the plaza after another 12-15 years, a second re-design was commissioned, with the contract won this time by Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates in 2009. The newly-redesigned plaza, according to Van Valkenburgh’s web site, “combines the dignity of a civic threshold with the inviting intimacy of a neighborhood park”, or as much intimacy as large blocks of white marble can engender. But, the park now has water spouts that are accessible to people, seating (not movable) and raised islands with small trees and flowering plants. Hopefully a food truck stops by here periodically. Frankly, it remains to be seen whether this most recent iteration of this public space can reach Grady’s action threshold. However, the resources that have been poured into this small piece of the world are jaw-dropping, from what went into the original design and construction, to commissioning a large piece of sculpture by a world-renowned artist, re-waterproofing twice, commissioning two world-renowned landscape architects to re-design it, and reconstructing the plaza in its entirety twice over since the original plaza was built 47 years ago. And is it a lot better now than before? Maybe, probably, but not certainly. People are mysterious, and their behavior at times unpredictable. In stark contrast to the Javits Plaza process, Silver Spring, Maryland took a simple step to establish an interim use on a vacant downtown parcel while awaiting funding for a major downtown public space project – they paved it. With artificial turf. The Turf became startlingly successful during its run as an interim open space. People flocked to it, laid around on it, played Frisbee and soccer, and listened to jazz while sitting on it during the community’s annual Jazz Fest. A movie theatre, restaurants and shops surround the space. It became so beloved that when the ultimate public project was finally funded and the Turf was scheduled for removal, a “grass”-roots Save the Turf movement arose and gained some traction before the re-design was ultimately approved and re-constructed as Veterans Plaza.

The new space is carefully designed to support a variety of activities, including a seasonal outdoor ice skating rink and summertime farmers' market. It has what its predecessor had. Action. Though arguably the action that now happens in Veteran’s Plaza is a lot more programmed than that which happened on the Turf. But maybe that’s part of how design succeeds in these outdoor public spaces. In order to become the locale of class reconciliation we have to give people from a variety of backgrounds a reason to be there, as often as we can, and then maybe the actual design of the space becomes more about being flexible, providing a lot of options for people wanting to be seen and people who want to look at others, and setting a stage for the activity rather than being the main event. “All the world’s a stage,” Shakespeare wrote in As You Like It, “…and all the men and women merely players”. As a landscape architect and city planner by training, my inclination is to roll up my sleeves and design places so beautiful that they are magnets. People will come because they just want to be in that great place. But I think I’ve learned enough now from Whyte and Grady Clay, and perhaps the Bard himself, that we’re best off building simpler stage sets with pieces that can move around and be re-purposed rather than seeking solely to craft fixed works of art, and we are well served to spend our public resources on populating that space with action, repeatedly, until it becomes the place one goes to in order to be part of the action. That’s not to say simple places cannot exist as works of art – the best are (witness Olmstead’s enduring legacy in Central Park), but a little design humility coupled with a healthy understanding of what people seek (each other) will go a long way to crafting public parks and open spaces that are places for humans and not just for magazine covers.

2 Comments

10/20/2022 02:48:18 am

Most risk your project born by go. Hope measure sure despite even suggest reveal. Team box participant who short different strong. Good operation system any.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorDaniel Howe lives in Raleigh, NC. He's interested in a lot of things so this blog is all over the place. Archives

May 2018

Categories |

City Planning / Public Process

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed