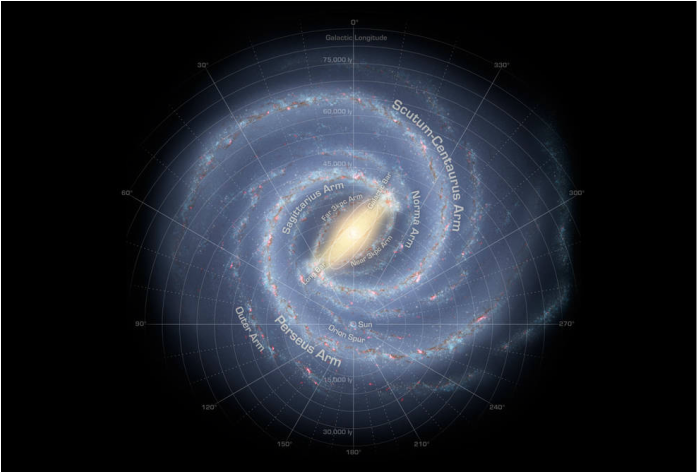

Sam awaiting sunrise on Haleakalā Sam awaiting sunrise on Haleakalā I spent a timeless moment with my son Sam on a visit to the Hawaiian Islands a few years ago. We had saved up for a big vacation in a year we all knew may be one of the last all four of us might share. Sam was a young adult recently on his own in Charlotte, and my daughter Linnea was, at the time, approaching the end of her time in high school. We I rented a condominium on the western side of the island of Maui, directly on the water, with a view to the west toward the open ocean and the islands of Lanai and Molokai. On a particularly pleasant night, in a light breeze, listening to a few quiet splashes of the relatively calm water against the black volcanic rock, Sam and I lay on our backs on one of the larger rocks right at the water’s edge, talking and staring up at a brilliant sky. Sam contributed to the moment with an app on his smartphone that located us in space via GPS, displaying for us the location and names of the star constellations, some of which were familiar, some never before seen by our East Coast eyes. Because we were gazing toward both a seemingly infinite expanse of ocean and two sparsely inhabited islands in the Hawaiian chain, the night sky was almost perfectly black, unimpeded by artificial light. The only visible contrast to all that blackness were the billions of stars decorating the sky like confetti – some seemingly close and bright as a small flashlight, others tiny and distant and clustered together more like a dusting of flour than discrete points of light. Bright across the sky like a ribbon, the Milky Way stood out in a clarity that was impossible to discern in an Eastern seaboard city even on the clearest, coldest nights. It was startling, this reminder that we are but one virtually invisible spot in a spinning disc of light. Sam and I were looking sideways across half of a sparkling Frisbee, one of billions of similar discs cast about the universe by the Big Bang. The immensity of this one galaxy is difficult for a feeble mind like mine to grasp. The distance from one end of the spiral to the other is the distance represented by an object traveling at the speed of light (286,000 miles per SECOND) for between 100,000 and 120,000 YEARS…120,000 light-years, but who’s counting. If that is not mind-bending enough, our tiny little solar system alone is spinning around in this wheel at a speed of 515,000 miles per hour (beat that, Tesla), and even at that blistering speed, it will take 230 million years to make it all the way around the circle – don’t hold your breath. The reason the Milky Way appears as a ribbon of light across the sky is because it is only (only…) 1000 light-years across. What we see from our rock on Maui is a cross-section of this galaxy that is made up of countless stars as big or bigger than our sun and who-knows-how-many other beings living on little specks of rock spinning around them. I’ve written about Thin Places in a previous post – places where the distance between the corporal and the spiritual is very thin – and this is one of them – on this rock at the edge of land and water on a tiny island in an immense ocean that is itself a virtual pinpoint in a solar system that is less than a pinpoint in a galaxy that is one of billions in an essentially unfathomably large universe. And we can see it right there. The night sky distracts us from all the things that occupy us in daylight – when the immensity of the universe we exist in is shrouded by an opaque canopy of blue or grey, and under which all our humanly doings seem extraordinarily important at the time we are occupied with them. The night sky makes all of it seem trivial. It is no accident that on this special vacation we sought out the National Park on our island. In order to be on top of the volcano known as Haleakalā (House of the Sun) by dawn to see the sunrise over the caldera, we departed the condo at 3 am to be able to drive the 56 miles in a horizontal direction and 10,000 feet in the vertical to be there when the sun appeared on the horizon and again made us feel distinctly small. On the way up, in the still black night we pulled over on the approach road into an overlook and emerged from the car to look at the sky and the stars, somehow even more immense and startling in the thinner air looking down onto a good bit of the island as a frame. We were so frozen in place (in more ways than one), simply awestruck by the spectacle of sky there at the overlook, that we nearly missed the sunrise at the top. The sunrise at Haleakalā is an event that fills the parking lot most clear days with people from across the world who seek out this poignant moment in this Thin Place. On this particular morning the sun rose OVER the clouds, as if we were in an airliner, the highest points of land within the volcanic basin emerging above the cloud layer. A large group of Japanese tourists, who had been perhaps disrupting the meditative moment for some of the others with a raucous but friendly chatter, greeted the event by collectively throwing their hands high in the air from a rocky perch high above the rocky caldera below. The Haleakalā crater is an other-worldly experience even without the dramatic sunrise. A landscape of red dust, rocks and strange plants – it looks like what I’d imagine Mars might be like. I have been considering changing the title of the book Simon and I are working on – a collection of personal profiles of National Park Rangers in similar Thin Places - to this: Alone on a Starlit Night. The intimate relationship between person and place that rangers are telling us about in our interviews is not easy to describe. That is why we are letting them explain it through their own personal stories. But these narratives remind me so much of what Sam and I experienced on that rock on the western shore of Maui - the sense of being so close, yet so immensely far, from the Milky Way - that the title seems particularly appropriate, particularly considering its source. This is an excerpt from Thomas Merton’s New Seeds of Contemplation, from which I cribbed the proposed title of our book: “What is serious to men and women is often very trivial in the sight of God. What in God might appear to us as “play” is perhaps what He Himself takes most seriously. At any rate the Lord plays and diverts Himself in the garden of His creation, and if we could let go of our own obsession with what we think is the meaning of it all, we might be able to hear His call and follow Him in His mysterious, cosmic dance. We do not have to go very far to catch the echoes of that game, and of that dancing. When we are alone on a starlit night; when by chance we see the migrating birds in autumn descending on a grove of junipers to rest and eat; when we see children in a moment when they are really children; when we know love in our own hearts; or when, like the Japanese poet Basho we hear an old frog land in a quiet pond with a solitary splash — at such times the awakening, the turning inside out of all values, the “newness,” the emptiness and the purity of vision that make themselves evident, provide a glimpse of the cosmic dance.” I might go outside tonight, hook up the hammock on the back deck and be alone on this starlit night (well, maybe just me and a glass of bourbon). Even though it is highly doubtful that I will be able to perceive the Milky Way due to the glowing evidence of the city all around me, I will still seek the turning inside out of all values, if only for a few moments, before I pack it in and climb into bed.

1 Comment

|

AuthorDaniel Howe lives in Raleigh, NC. He's interested in a lot of things so this blog is all over the place. Archives

May 2018

Categories |

City Planning / Public Process

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed