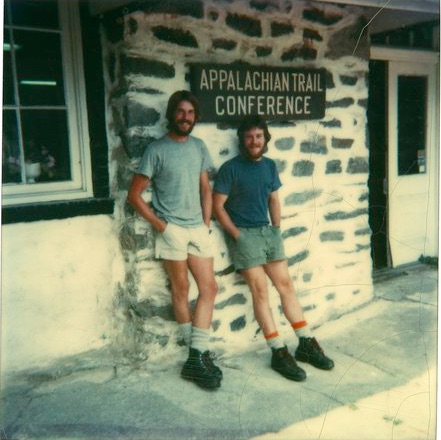

Dan Howe and David Brill in 1979 at Harpers Ferry WVA during their through-hike of the Appalachian Trail Dan Howe and David Brill in 1979 at Harpers Ferry WVA during their through-hike of the Appalachian Trail This is the first post of the Centennial year of the National Park Service that will culminate in the birthday celebration August 25. In addition to pursuit of our project to document the personal stories of NPS rangers throughout the year, I'll be posting periodically on some of the more amazing and wonderful parts of our National Parks System...perhaps a few you might be introduced to for the first time. The National Trails System Act was approved by Congress on October 2, 1968. The purpose of the act was to establish, under to aegis of the National Park Service, a series of historic trails that allow visitors to retrace the steps of pioneers, explore the three major mountain chains that exist on our continent, and pass through areas of our country of particular historic or cultural significance. 30 Trails are established under the act including this sampling:

The Appalachian Trail, in particular, represents a unique relationship between over 30 private trail clubs, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, a not-for-profit coordinating agency who manages the trail under contract to the National Park Service, and in cooperation with the NPS and a variety of other Federal agencies including the National Forest Service and the US Fish and Wildlife Service. Conceived by urban planner Benton MacKaye in 1921, the Trail was finally protected in its entirety in 1971. Along with my great friend David Brill, I through-hiked the AT (walked its entire length in a single 5-month stretch) in 1979. Still the most popular mountain trail, the AT attracts millions of visitors each year, with approximately 3000 people likely to attempt a through hike in 2016. This is a substantial increase since our hike in the 70's, when less than 1000 people had completed the trail since its creation. Most National Scenic Trails exist in partnership with a private organization that advocates for trail protection, raises funds, builds and maintains sections of trail and promotes the expansion of the Trail system. See an interactive map of the entire AT. A shorter, but equally intriguing trail system is the 450-mile Natchez Trace. The Trace was a trade route that extended from Nashville, TN to Natchez, MS along the Cumberland, Tennessee and Mississippi Rivers. Created by native Americans, it was used by white traders, soldiers and migrants in journeys south and west of Nashville. Today the National Park Service maintains not only a series of walking trails along the historic route of the Natchez Trace, but also the Natchez Trace Parkway, a 444-mile limited-access parkway built during the Depression by Civilian Conservation Corps workers. Today, in addition to the driving experience, hikers can walk any of 5 trails that make of the Natchez Trace National Scenic Trail, totaling 60 miles of prairie, swamp and forest. Learn more about the Yockanookany Trail (say that five times fast...), the Potkopinu sunken trail, the Blackland Prairie Trail and other parts of the Natchez Trace National Scenic Trail. For a complete list of the entire National Trails System, click here.

1 Comment

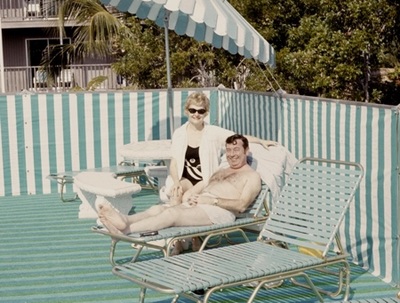

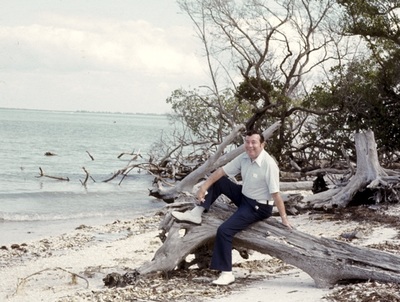

The 70's version of Dan at Christmas The 70's version of Dan at Christmas Of the many Christmas landscapes that I’ve experienced, none is as weird as Christmas in Florida. I was in college at the time in Virginia, and road-tripped with a friend down Interstate 95 to meet my parents in Orlando for the holiday. They’d decided that it might be fun to experience the yuletide under a palm tree. My parents, Millie and Jack Howe, are both from the Midwest, where Christmas is often frigid and rarely white. For much of my childhood we lived in St. Louis, with excursions for several years to the New York metro area and to eastern Pennsylvania where I went to high school - different places with a similar December climate. The family tradition was to stay home with the heat on, look skyward hopelessly for snowflakes, erect the three part fake Christmas tree the weekend after Thanksgiving, make a lot of cookies and load the underside of the tree with an embarrassing pile of gifts that we would open ritually in our pajamas on Christmas morning with Grandpa. It was a good tradition, despite the disappointment of cold without snow just about every year. Between St. Louis, New Jersey and Pennsylvania the holiday routine was consistent, so the idea of a Florida Christmas was just a small bit disturbing. But who was I to argue with Mom and Dad? Let’s go for it. My father was suffering with a rapidly advancing case of rheumatoid arthritis at this point in his life. He understood what the future might hold for him and I believe the Florida Christmas was his idea. He was trying to pack in as many adventures as he could before his physical condition would start to preclude simple things most of us take for granted like walking and buttoning one’s own shirt. We stayed in a small place in Orlando that was located in what used to be a citrus grove. In the back yard of the unit we were renting was a grapefruit tree, and the rental came with a basket-like thing with grabbers on a stick, the perfect tool to pull the Yule grapefruit down off the tree and have it drop nicely into the basket for easy retrieval. I still remember my father sawing out the grapefruit sections with a butter knife and marveling at how short the distance was between this particular fruit’s perch on its stem and its final disposition at the breakfast table, compared with the well-traveled and somewhat more road-worn orbs that we’d pick up in the produce section of the Schnuck’s back home. After breakfast we donned our Christmas shorts and t-shirts and headed to the then-new Walt Disney World theme park, where a series of larger-than-life cartoon characters greeted us dressed in what must have been stifling costumes of red velvet and white fur, the sound system all around piping in startlingly incongruous songs about sleighbells and snowmen while we wiped our brows in the warm sun between adventures in Space Mountain and Epcot. Part of that trip also involved a visit to Cypress Gardens, a now-anachronistic water resort in south-central Florida then widely known for its beautiful tropical gardens and water-skiing show featuring bikini-clad skiers. I daresay that moment represents the first and probably the last time I will see Santa Claus doing a spread-eagled leap off a ramp on a set of water skis while holding onto a tow rope from a powerboat. The best memories I have of the Florida Christmas were formed during the several days we spent on Sanibel Island, on the Gulf Coast near Ft. Myers, Florida. At that point Sanibel was still a mostly undeveloped island upon which existed a series of small homes and tiny motels and a sandy single two-lane roadway, the island heavily protected by stern land use regulations its citizens imposed on the building industry and by the eyebrow-raising toll exacted when crossing the causeway from the mainland. We decorated a croton plant with a few colored lights inside our tiny motel room and exchanged a few gifts, without Grandpa this time, to mark the day itself. But the island was much more a magical place than Disney World, with Santa’s gifts strewn all across the beach in the form of beautifully formed seashells, which we collected greedily, as if somehow they’d run out if we didn’t get them right away. The warm breeze off the Gulf stirred the palms, and flocks of seabirds passed overhead, looking to roost nearby in the “Ding” Darling Wildlife Preserve as the sun set below the horizon in the Gulf. Christmas dinner was simple fare from one of the local restaurants, the building covered with bougainvillea that had been decked out with multi-colored Christmas lights, as if such a plant needed any more decoration than nature had already given it. Tropical as it was, this holiday was still Christmas, and we enjoyed each other and our treasure-trove of seashells. Then we folded our beach chairs, brushed the sand off our bare feet, and returned to our respective homes – me to Virginia to look for signs of white on the Blue Ridge come January, my sister to Bloomington, Indiana, and my parents back to St. Louis, where in the Italian section of the city every architectural feature of every house in every neighborhood was covered with as many colored lights as the owners could afford to buy and power, in celebration of the birth of the Christ Child. In keeping with this heritage, I try to keep some downward pressure on the ever-escalating property values in my own neighborhood by stringing lights on everything I can find in the yard and on the façade of my house during the season. I must apologize to those who think that the tasteful single candle in each window and the lovely wreath on the door constitute Christmas decorations. I respectfully disagree. This year apparently the squirrels have taken offense at my overindulgence. They ate through the wires on several of my strands, alas during a time when the electricity was off. As the temperature approaches 70, with 75 degrees predicted for Christmas Day, suddenly the Florida Christmas is closer in mind than it’s been in some time. I think my own family may be in shorts right here in Raleigh on our Christmas hike this year, much as my mother, father and sister were on Sanibel back when my father could still walk in the warm sand and button his own shirt. Somehow despite so many happy, chilly, snow-bereft years with my parents and my sister in our cozy home with the heat on, the holiday I seem to remember is the incongruous one. I still hold out hope for a white Christmas here in North Carolina, despite our warming climate. One year we actually almost had it. In a bizarre turn of events Wilmington, on the usually-warmer coast of North Carolina, was buried in a freak snowstorm on Christmas Eve, with snow extending west as far as Goldsboro, only to turn to a cold rain at the Johnston County line, about 40 miles east of Raleigh. Sigh. Without palm trees, grapefruits and seashells, the warm weather we've experienced recently is not quite as welcome this time of year in the Piedmont as it was on our Florida adventure. But it’s still Christmas, and enough lights have survived the squirrels to glisten through the rain outside the window and make me remember that, even though the Bing Crosby Christmas landscape of snowmen and sleigh bells is a pipe dream for us this year, the one we have is still pretty nice. It will be in the 70’s with a few thunderstorms predicted on the holiday, and I will walk with my family and neighbors on Christmas Eve in a t-shirt and a rain jacket down to the corner to see the live Nativity at the Hayes Barton Baptist Church. We’ll feel sorry for the wet burro and the little sheep, and the poor angels from the youth choir standing in the rain on top of the manger. We’ll still sing Christmas carols and give Luna a new dog toy, and we will all continue to wish for a white Christmas someday. This year I will also think about my parents’ wild idea to see Santa on water skis, the wonderful gift of seashells on Sanibel Island, the warm air and beautiful sunsets, and I will remember the two of them and miss them. Happy Christmas to all. May the New Year bring you peace and joy.  Photo credit: Phillip Capper (Flickr) Photo credit: Phillip Capper (Flickr) In 1989 my wife Loretta and I, and our friends Cece and Bill Ussler hiked 12 miles into the backcountry of Canyonlands National Park in search of an ancient cave painting – the All American Man. Recent radiocarbon dating of the pigments used in this ancient pictograph places its creation somewhere in the 14th century. Canyonlands is a landscape of sandstone, carved by wind and water into the kind of sculptural rocky shapes that Utah puts on its license plates. On our way we came upon an Anasazi cliff dwelling beneath a sandstone overhang. It was close to the trail, but there were no railings, no concrete walkways, no signs directing or restricting our access. It was as if we were ‘discovering its existence, as some early explorer in this part of the West did. I remember feeling hesitant, approaching as if trying to avoid stepping on a grave in a cemetery. Beneath a giant rock were the remains of a house where people had lived, raised children, stored food, built fires to warm themselves - almost 800 years ago. As I stood in the remains of the kiva, I was stunned by the magnitude of time that separated me from the last person who lived here. It is the same feeling I often get as I look up toward Orion’s belt on a clear winter night - smallness in the face of time and distance. But in such places this gulf of time and space does not isolate me from the owner of my kiva or from the Big Bang, but somehow connects me to them, the separation between the corporal and the spiritual becoming a thin veil. There is a Celtic Christian term for the rare locales where the distance between heaven and earth collapses. They are called “thin places”, and here in the kiva the wall of time and culture that separates me from the Anasazi, the Ancient Ones, who so mysteriously disappeared from this landscape, fades. This is a built place. So often people seek thin places in nature – waterfalls and craggy peaks, dark forests and seashores. But we humans have built many landscapes, interior and exterior, that similarly pare the distance between the sacred and the solid. Visit the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC at dusk and you will understand. Another such place is the Flight 93 National Memorial in southwestern Pennsylvania, or St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City. Great architecture or landscape architecture can do this. But a simple cannon placed in a Virginia meadow can do the same. My friend Paul Morris, a landscape architect from Atlanta, said this in the context of a conversation about sacred places: “Places are static – meaning comes from people.” Sometimes the physical environment does not have to be striking to be powerful – a multi-community greenway in Memphis, Tennessee is not so much about the bicycles and pedestrians who may use it as it is about a single gunshot in April 1968 and the racial divide that has characterized the community, and how the path knits parts of the community together that have been separated ever since. What Paul is saying is that a place must have meaning to people in their own lives to capture a sense of spirituality beyond its physical space. I’ve felt this on the summit of Mt. Rogers in Virginia, the highest point in the Commonwealth. The final climb to the summit is not difficult. There are no views from the top, just a large rock with a USGS marker embedded in it surrounded by spruce and fir trees. But the approach to the summit is through a dense remnant of the Canadian-zone vegetation that once covered much of the East and Midwest in the wake of the last ice age. Here in the Southern Appalachians such forests are fast disappearing and are limited to the highest, coldest elevations. This forest is somehow quieter than the rest of the oak-hickory forest that surrounds the peak. Everything is moss-covered. It is dark, even on a bright day, and smells of balsam, like Christmas. Its meaning for me is wrapped in every fairy story I experienced as a child and with my own children as an adult, lands of mystery and strange creatures – wizards and Wookies. It reminds me of how colored lights on a dark night make me feel at that time of year. The tactile quality of the moss is comforting, like a blanket. God, or thousands of years of forest succession, created this place. A human built a trail here so I can experience it, but otherwise the hands of people have contributed little to this thin place, but there are many skillful designers packing meaning into landscapes throughout the world. Some are grand and historic, inspiring, like Andre le Notre’s Avenue des Champs-Élysées terminating in the dramatic Arc de Triomphe in Paris. Some are contemporary and personal even as they draw a crowd, like Anish Kapoor’s Cloudgate sculpture in Chicago. In it you can see yourself and the skyline of the city, reflected together. Alfred Runte, in his excellent book National Parks – The American Experience, makes the case that the National Park movement started in this country as an attempt to capture and preserve the soul of the new nation before it was overwhelmed with industry and commerce. The leaders who advocated for the preservation of special landscapes set out to create temples to remind us of what differentiated America from Europe with its grand cities and architecture. What they preserved started with the great Western landscapes that defined what America meant to its citizens at the time – the romantic notion of freedom within God’s creation. For the intervening 100+ years, the Park Service has wisely expanded this notion to preserve not just that moment in history, but a pastiche of soul-markers along the way – battlefields, homes, factories, monuments – that have meaning for people. It is no accident that I’ve discovered many thin places in my wanderings through the park system, from the Vietnam Memorial in Washington, DC to a craggy outcrop on the Appalachian Trail in Virginia overlooking the James River valley. When we are at our best, we humans have the ability to build mystical places that can rival the emotion engendered by a view of Half-Dome or the feeling of the mist rising from Niagara Falls. This mystery arises from our shared stories, good and bad, of freedom and conflict, wisdom and blindness. If we pay close attention, maybe we can learn from the stories of people who lived long before us, and also from the thin places not created by the hand of man, understanding in some small way how a copse of conifers atop Virginia’s highest peak can transport us to another world.  This year the Japanese maples (generally Acer palmatum species) have had an extraordinary fall. Because the weather has been warm and wet, the Japanese maples have hung on even past the emptying of the foliage on the pecan trees - usually the last to drop their leaves. Their spectacular color, combined with the fact that only they, the crepe myrtles (Lagerstroemia spp.) and some oaks are still hanging on into the first days of December, helped me pay particular attention to them this year on my walks around the neighborhood in the morning with Luna the dog. Scientists say that most trees are photoperiodic - the length of the day relative to the night rather than the temperature is what triggers the changes in metabolism that begin the process resulting in the spectacular colors that we see - yellow, orange, red, purple. Japanese maples are typically small trees, sometimes very small in the case of the "dissectum" varieties - the cutleaf Japanese maples. All of them have lovely shapes, and this year luminous red or red-orange color. I have several varieties in my small yard. The winner of the eye-popping color contest this year is a purple-leafed maple (Acer palmatum atropurpurea) whose leaves come out purple in the spring and gradually fade to a dark green/red before transitioning to a dazzling scarlet this fall. The other surprise was a small seedling of the coral bark maple (Acer palmatum Sango-kaku) whose normally bright yellow fall leaves have a decidedly red-pink cast this year, unlike its parent tree. I feel fortunate to be able to see this - fall must be an entirely different experience for people who are sight-impaired - and even more fortunate to have noticed this and paid attention to it over the past few weeks. We move at a rapid pace through our world - on trains or buses, but mostly in this country in our cars. The amount of time we are not either flinging ourselves headlong through our network of highways, or moving back and forth in a small space in our offices or workplaces or homes is small. But if you choose to spend more of your day moving through the landscape at a walking pace, so much more is revealed that would otherwise have been a blink in passing through the windshield at 40 or 50 miles per hour. For me, the revelation at this pace this year has been the proliferation and immense beauty of the Japanese maples planted in people's yards along my path through this part of Raleigh. The richness of their color and the emphasis it brings to the shape of the tree against what is otherwise now a dull green or brown landscape is dramatic, and I feel as if I've been given a gift because Luna pulls me out on extended travels at walking pace in my world. I am reminded of my experience hiking the Appalachian Trail, where this gift was drawn out over 5 months in a journey that led through the mountain chain from Georgia to Maine, from winter to spring to summer to fall. Almost all long-distance hikers struggle to describe the experience after they've returned to the life of fast and slow, driving and sitting. An extended experience at 2 miles per hour is an opportunity to see what you have never seen before - the wildflower called a showy orchis hiding in a wedge of rock at a switchback, the particular color green that the forest takes on in April that can only be described as early spring green, as the buds on the deciduous trees slowly unfurl into leaves, the quick movement that turns what appears to be a twig into a swift litlle lizard, dashing for cover. It is hard to explain how much more detail is available in the landscape at walking pace, and how repeated experiences with it teach us things. I hiked the AT at a time before access to hand held communication devices kept us connected wherever we go. We found that over time walking in the forest we developed a sensitivity to our surroundings, particularly the weather, that was nearly as accurate as we could have accessed via smartphone today. The smell of the air, the color of the sky, the clouds and how they were changing would tell us a lot about what the weather was to be like the next day. I can still recall the deadness of the air, the immense stillness, that preceded the remnants of Hurricane David before it slammed into us in New England. I also still recall the absurdly good-natured group packed tightly into a three-sided shelter that night as it rained sideways, our tent flys and ponchos strung across the open side of the tent in a futile attempt to keep it from raining inside. One hiker pulled out a harmonica and launched into what would become the improvised "Leaky Shelter Blues". Humans were designed to move at walking pace, and I am reminded of the observation skills we are born with as I spend extended hours at this speed. Our bicameral vision gives us perspective, shape and spatial awareness, and a sense of distance and movement. We also hear more and can look at and listen to longer something that might catch our attention in the landscape. I like operating my automobile as much as the next person - a road trip is more fun for me than for my wife Loretta, but I would never have noticed the Japanese maples this year at 60 miles per hour. Safety requires that we scan the landscape ahead of us quickly when we drive - looking for hazards. If we're lucky we can glance at something along the way, but it is gone before we get a chance to really LOOK at it. I look forward to seeing what the winter will bring. With so many trees around here, the summer obscures much of what we've built, and in the winter a lot of how people have chosen to live in this place is exposed. Luna and I will set off at our two, maybe three mile-per-hour pace and watch for it as we go.  I am working today on Maria Beotegui's story. Maria is an Argentine immigrant to South Florida. As I try to relate the story she told us on our visit to Biscayne Bay, I think about what she and her family have brought with them from Argentina to the US. Maria, her mother and her brother are all National Park Rangers. Theirs is a quintessentially American story of struggle, difficulty, hard work and ultimately - success. Maria's passion is bringing the rich world of Biscayne Bay to urban youth in the Miami-Dade area, many of them immigrants or children of immigrants. As I will note in her story, Maria understood at an early age the differences in culture between the fast-paced world she lived in here and the Argentine culture she left behind. She notes how striking it was, on a visit back to Buenos Aires to visit family when she was a youth, how happy people seemed to be despite living with so much less than people do here in the US. This is not the first time I have heard that theme expressed. My own son Sam said as much when he returned from a church youth group trip to Matanzas, Cuba when he was 16. He marveled at how open, how loving youth were in Matanzas - both with each other and with their new American friends - and yet how little material wealth they had in comparison to their visitors. Maria's goal is not only to understand this difference so she can relate to her young constituents in Miami, but to help her own children find honest happiness in their own hearts in the midst of this bounty of material wealth in the US. Maria also talks about her South Florida landscape as being "family". She says "I love nature anywhere I go. I really don’t feel out of place or uncomfortable anywhere in nature. But if you are with your family, it's different. That’s how I feel at Biscayne. I am with my family. I know the names of all the trees and I’ve known them all my life, and the salt water here it flows through my veins. I've gone swimming in the water, I’ve looked under the rocks. It’s a big part of me, of who I am, and I can’t imagine being too far away from it for too long. Like family." In a time of fear, where we are considering all outsiders as a threat, I try to remember the look in Sam's eyes as he talked about his journey to Cuba. It was hard for him to believe that people could welcome him so openly, so lovingly. I think it really changed him, and he's a better, kinder person for it. Perhaps it's because the Cubans Sam met, the Argentinians Maria visited, felt like they had very little to lose. What they had, no outsider could threaten - love, laughter, family. As we look toward immigrants with a wary eye, I think it is important to remember that our suspicion is perhaps filtered through a burden of stuff that we are worried they may ultimately take from us. If we stop for a moment and think about what they might bring to us - love, laughter, family - maybe our better nature might win out over our fear. In a Pew Research Poll taken earlier this year about half (51%) of the respondents say immigrants today strengthen the country because of their hard work and talents, while 41% say immigrants are a burden because they take jobs, housing and health care. The share saying that immigrants strengthen the country has declined six percentage points since last year and I suspect would be even smaller in the wake of the Paris attacks and the exodus from Syria. We are scared that immigrants are somehow going to take something from us. We measure their benefit in terms of hard work and talents, but I think we forget what else they bring with them, particularly from Latin cultures - the sense of happiness that comes from feeling like we are all part of a family. We care for each other, we get to know each other, and we give each other help when it's needed. That's what family is all about. This week, the French were our brothers and sisters, and we stood in solidarity with them as they struggled through tragedy, just as they did for us after the 9/11 attacks. But it was not long ago that the French were not particularly revered in this country. Remember "freedom fries"? But just as we embraced them, we stiff-armed Syrian refugees who, arguably, have suffered even more greatly from terror and loss. I envision America to be a place where visitors from other places can arrive here and marvel at how happy people are, whether we are well-off or not. I am not certain it is that kind of place today. Moving into this year's Thanksgiving week, I hope we all can remember what to really be thankful for - people - who love us, laugh with us, help us when we are in need. I am thankful for my family, for my friends who are like family to me, for the place where I live. Like Maria, I feel connected to it just like family.  Our house in Raleigh's Five Points neighborhood. Our house in Raleigh's Five Points neighborhood. My wife Loretta and I, and our children Linnea and Sam, have lived in this house, in this neighborhood in Raleigh, since 1992 when Sam was 2 years old. During this time the 'hood has evolved. The property values have grown dramatically, and more than once in the span of time that we lived here we have considered cashing out and moving someplace else. But we haven't. Because, to be honest, there is no better place on earth than the one we are embedded in. Yes, we could probably have had a big house with a larger porch on a plot of land that gives me opportunity to grow all those dwarf conifers I have always wanted. We could have the "play room" in the basement that our children have always pointed out in other people's houses. We could have a garage. No, we really don't need a garage. Our choice was to embed ourselves in a place - both the micro-place within our four walls and a more macro-place in what we call our neighborhood. It is this embedded connection to place that we simply could not duplicate if we cashed out and sought another house in another neighborhood, no matter how "nice". Our house was smallish to raise two children, but we did it without sacrificing much. Now as our daughter prepares to leave for college and beyond it is perfect. No "down-sizing". What we gained were relationships with people around us - many of those who participated in Sam's play group when he was a toddler (he's 25) are still around. We went to the funeral of one young man this past year. We've watched our neighbors across the street renovate their house, live a young person's life for a while (they traveled a lot) and now raise their little boy and advance in their respective careers. We've watched the big sweet gum across the street come down (Thank you, Jesus...no more gum balls!) and many of the dogwoods die, even as our hemlock has grown from Christmas tree size to forest material. We've watched Halloween become such an event that we have to close off both ends of the street so there is room for the pig-picking before the young'uns set out on their trick-or-treating. We've seen our own house get re-built stick by stick from the inside as we changed and molded it to our personalities and lifestyle, and our little yard start out with a play structure and swings in the back and evolve into a big screened porch, a terrace and fire pit for us and for Linnea's teenage friends. People are adding on and even tearing some houses down and replacing them. A wistfulness rises only to be tamped down by the reality of our neighborhood as a living thing - constantly changing. That is a good thing. It is a common practice in this culture where houses are a commodity, supported by a governmental subsidy for taking on greater mortgage interest, to consider them disposable - our neighborhoods the same. When things get rough we cash out. I've heard the wisest way to grow wealth from this "investment" is to sell your house after a few years, buy another one, then re-sell it and keep on doing this until you've accumulated the largest possible house you can imagine in the best possible neighborhood. The reason a large house is valued more than a small house is that we buy and sell our homes by the square foot, roughly comparable to selling your car by the pound. Because of this headlong rush toward turning our homes into commodities and investments, we are losing the human connection to the landscape of both home and neighborhood that so characterized this country for so many generations. We paint everything beige to please the next owner (who probably doesn't like beige any more than we do). Part of what has made our relationship with this particular micro-landscape so valuable has been our ability to watch our children grow here, to watch other people's children grow, to be part of the gestalt of a place that is more than the sum of its houses. We've benefited in ways not easily measured from our connection to this place. What we may have given up in square footage and equity we have more than gained back in memories, in history, in meaning that these brick walls and narrow sidewalks hold for us. This is why we don't sell the American National Parks for development, and go off and buy a bigger piece of land with the proceeds. There is meaning in these places. They are unique and we all benefit from being in them - soaking up the history of a place, of a people. We lose it when land and buildings become only a vessel for growing wealth. So think about sending down a few roots. Make your money on the stock market or buy a lottery ticket and re-introduce yourself to your home - make the connection. We arrived back in Raleigh late Friday from our whirlwind trip to Asheville to present the RANGER project at the Association of National Park Rangers (ANPR) annual meeting - the Ranger Rendezvous, held at the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly in Black Mountain. The meeting was held in an immense 1910 building on a large campus with a spectacular view of the Black Mountains in full autumn color, crowned by Mt. Mitchell, highest point east of the Mississippi River. The old school porch festooned with rocking chairs brought me back to my "dirty dancing" job in the Poconos at Mo-Nom-O-Nock Inn, where a very similar porch with rockers opened to a view of three states. Only in my dreams did the actual experience mirror the movie, but I was amazed at this large YMCA facility that I never knew existed. They were expecting 1000 guests across the several buildings on the campus for the peak leaf-peeper weekend weekend here in the Southern Appalachians.

See the introductory video for the presentation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mo-PrOGCTn0 We presented in a small room, that happily was packed with all seats taken. We talked about why we were pursuing this project, about the rangers we have profiled so far, about ourselves and our hopes for the project going forward. Lucky for us, people were very willing to talk and we had a lively conversation about the project. Important takeaways for me were that personal stories can maybe be too personal - we need to emphasize the connection of people and place and not allow people's compelling personal narratives to distract too much from the connection with the parks. I think that is the advantage of narrative - it allows a richer relationship to develop between the two. The short 3-minute videos we used to introduce our audience to the people we have profiled so far are effective, but make it harder to make this connection in such a short time. We also talked about who a "ranger"is. There are different opinions in the Park Service about this, but I'm hoping to keep the definition broad - people who have administrative and facility responsibility are fair game for profiles as well as the traditional protection, resource and interpretive rangers are. We also talked about the importance of ensuring that rangers are not exploited in a headlong pursuit of profit. I think with the economics of a book project there is very little danger of that to start off with ;), but I understand the concern, and agree that it's critical that this be a celebration and elevation of rangers, not a vehicle for commercialization. It's not why we set out on this and I'm confident we'll be pushing this in the right direction. Our next step is pursuing a non-profit partner to join with as we seek funding to produce the rest of the book. I think this can be a win-win-win for our partner non-profit as well as a major contributor looking to give an important gift to the parks or rangers in the Centennial year. Our concept is to engage a contributor to give a gift in the form of the production cost of the book to our partner non-profit, who will contract with us to complete and print the book. The proceeds from the sale can then be cycled back to the non-profit as a revenue stream for as long as the book sells. That's the objective, and with luck we can be successful at finding the right partners. Being among rangers in such a beautiful place reminded me why we started this - fascinating people wholly engaged with the magnificent places that have such rich meaning for all of us. It was a great day, made greater when, on the way back, we chose to drive a long ways on the Blue Ridge Parkway, ultimately standing on the highest point east of the Mississippi, to look down in 4 directions at the magnificence of the Southern Appalachians, from Mt. Rogers to Clingman's Dome, in full autumn blaze. Simon and I leave for Asheville today. We are presenting on Friday at the Association of National Park Rangers (ANPR) annual meeting - the Ranger Rendezvous - about the book project. Our hopes for this trip are (1) that we get good feedback from the ranger community about the book project, (2) we get a number of suggestions of rangers we need to profile around the country, and (3) we get the chance to see some fall color, since we'll be in the NC mountains in peak fall season. If eyes are glazing over during our presentation and we hear a lot of "good luck with that" comments we'll have to regroup, but as an optimist I'm hoping for encouragement. I want to find out where we might be going into sensitive territory, where we might not be touching on important aspects of living life as a ranger, where we may be bordering on the trite. I realize rangers themselves are not the only audience for this book, but it's important to us that we respect the reality of their lives, and understand what is important and not important to them. I feel that the sum of these profiles will add up to a story in itself - a story that's still a bit of a mystery - and so, to do a good job with these individual stories, I feel Simon and I need to understand more about the overall culture and context within which these individual tales emerge.

This also starts the public phase of this project. To this point I've had a number of phone calls with people across the country, consulted my friends here, worked hard on the 4 profiles we've completed in two parks, and worked with Luke McMahon, Jenn Bird, Simon Griffiths and Marc Harkness, our Asheville designer, to craft the material you see here on the web site and in the presentation we'll be giving to the ANPR. After Ranger Rendezvous we intend to start building support for the project, advertise the web site, get onto social media and begin looking for a publishing option. I recently had the opportunity to spend time with Justin Martin, author of Genius of Place: The Life of Frederick Law Olmsted. Justin was a great help, and his understanding of the publishing and writing industry was invaluable. Gratifyingly, Justin seems to think a publisher would likely be interested in this book. Up to this point we had held the traditional publishing model as "Plan B", while thinking about self-publishing or partnering with a parks-related non-profit, but now I'm mulling working both sides at the same time. We'd still love a partnership that would result in some of the proceeds of the project going back to the National Park Foundation, the National Park Conservation Association, or the ANPR. But, ultimately, we want the book to be out there so people can read it and see Simon's photographs. I'm admitting also to a bit of concern about defining myself as a "writer". I have been a number of things - a planner, a landscape architect, a bureaucrat - but now as I enter the "third third" of my life I find what gets me up in the morning is crafting these stories. I am lucky to have as my closest friend a real writer, David Brill, who also happens to be the person I shared by through-hike on the Appalachian Trail with. He is the rare author who has found a way to really live the life - working as a free-lancer out of his incredible cabin in East Tennessee's Cumberland Plateau. Dave's always been an inspiration to me in many ways he probably doesn't even know about, and I am grateful for his support. I think I'd make a lot more money being a development consultant or even an organizational consultant for governments, but my passion is getting ideas down on paper (or in the word processor). I remember spending probably absurd amounts of time in my prior career crafting memos to be succinct, to lay out clear points of decision for elected officials without overloading them with detail, to frame an issue with many facets in a short document. I also remember spending a lot of time trying to listen well enough to get what people were (fill in your emotion: angry, frustrated, excited, worried...) about. I hope if I match the listening with the telling in an effective way I might sometime be a little more comfortable calling myself a writer. For now, I am on a steep learning curve, and I appreciate having as accomplished an artist as Simon as my partner in this project, and truly great writers like Dave Brill and Sylvia Adcock (my Pulitzer-Prize-winning neighbor and friend) helping me out. For at the end of the day what we are seeking to do is art. This isn't a report, it's a tale and needs to hit you on the right side of the brain, in a place where your senses and emotions are in control. Embarking on a journey into the dark valley of web site design, what you see here is the first message from the wilderness. There will be quite a bit here in this blog over the next few months about a book project, RANGERS - Personal Stories of National Park Rangers and the Landscapes They Protect and Preserve, which I am undertaking in partnership with my friend (and neighbor, and bicycling buddy) Simon Griffiths. So far we have interviewed four people in two National Parks. I admit to being a little bit of a junkie about all things National Park, but even considering that predisposition to love this stuff I am finding that these people blow me away. They are smart, articulate, dedicated, and despite a lot of personal challenges have built a unique and rich relationship with the place that they work in - a marriage of person and place. This is what the book is about.

To this point we have done all this on the cheap - driving to Florida and staying on Jay Johnstone's floor in Homestead (Thanks, Jay!) - taking the long drive to Morgan County, Tennessee (twice!) to spend time with Matt Hudson, and hang there with my Tennessee guru, David Brill, who is himself an accomplished writer. We stayed at Dave's cabin (probably a misnomer - it's bigger now than my house in Raleigh) on the Cumberland Plateau high above Clear Creek. In two weeks or so we will make a presentation to members of the Association of National Park Rangers (ANPR) in Asheville, NC. I am excited about presenting to this community. It is my hope that we will solicit some useful feedback and with any luck a long list of people we will "need to talk to" in the Parks. This also begins our fundraising effort, and over the next few months we'll be reaching out to organizations, individuals and companies who many want to make a Centennial gift to the National Parks in 2016 in the form of a contribution toward the production cost of this book. Thank you for visiting the site and reading this. In order to put a presentation together for ANPR I tried to weave Simon's excellent photos, Luke McMahon's video and the Rangers' individual stories into a multimedia presentation, and it quickly morphed into this entire site, with some text, some video and some photography for you to peruse. Let me know what you think. This is my first effort...please be kind. Hopefully I can continue to refine and make this a better platform not only for the Ranger project, but for the wide variety of things I am interested in. I'll look forward to hearing suggestions! |

AuthorDaniel Howe lives in Raleigh, NC. He's interested in a lot of things so this blog is all over the place. Archives

May 2018

Categories |

City Planning / Public Process

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed